Tuskegee Airmen: The pioneering black pilots whose excellence helped desegregate the US military

By the Second World War, black men and women in America had fought against brutal slavery, prejudice, bigotry and violence for centuries just for the colour of their skin.

And yet, despite being treated as second-class citizens, many still wanted to serve their country only to be told their contribution to the war effort wasn't as valuable as their white counterparts because they were considered "inferior".

The pioneering black airmen and groundcrew of Tuskegee, Alabama, changed all that and in doing so paved the way for the desegregation of the US armed forces.

Excellence will overcome obstacles

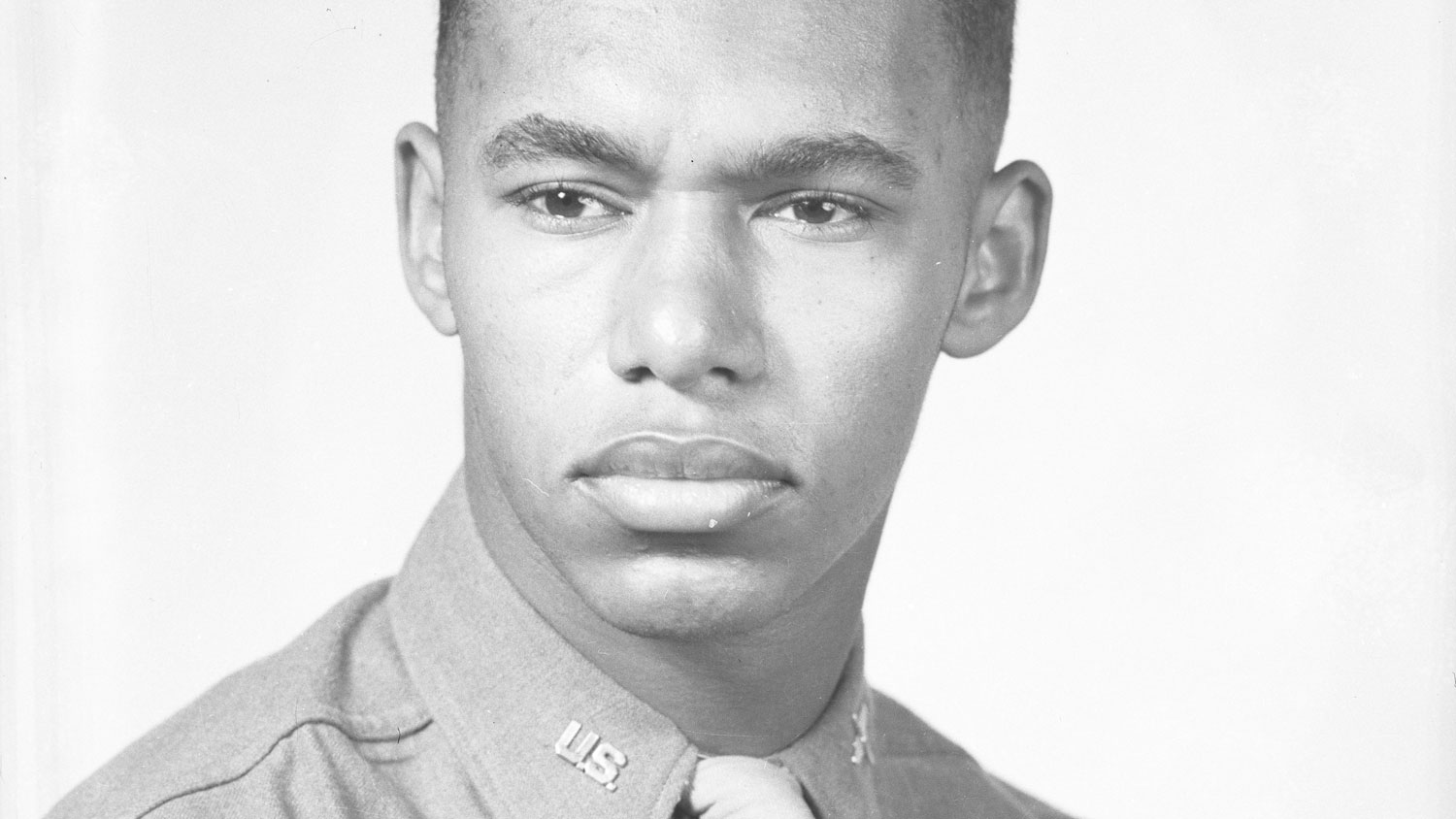

The late Captain (Retired) Roscoe Brown served as a squadron commander of the 100th Fighter Squadron of the 332nd Fighter Group during the Second World War.

He was one of the Tuskegee Airmen – the first black military pilots in American history.

In a 2012 interview with journalist Michel Martin for NPR (National Public Radio), the veteran-turned-doctor explained what it was like to be black during the Second World War, saying: "One of the things that a lot of people don't realise, just how rigid segregation was at that time.

"People could tell you to your face that you... couldn't go into a theatre, you couldn't buy a house, you couldn't get in the air force.

"So, therefore, what we did helped to break those barriers."

He explained that the Tuskegee Airmen knew they had to be "better than white people" to be treated as equals.

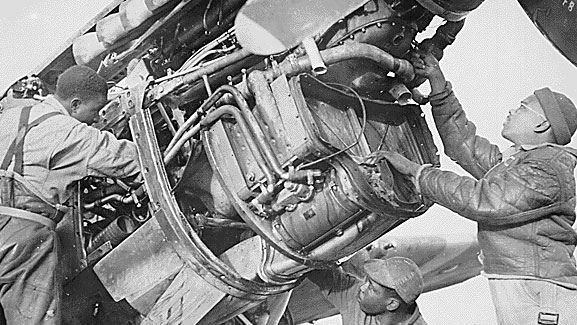

Despite popular belief, those known as the Tuskegee Airmen (a term created by author Charles Francis in his 1955 book The Tuskegee Airmen – The Story of the Negro in the US Air Force) weren't all pilots.

The term is also used for the military and civilian men and women of a variety of races – such as Latino, Native American or white – who provided ground duty support and played their part in the Tuskegee Experiment.

Referred to by the airmen themselves as the Tuskegee Experience, the Army Air Corps' first programme to train enlisted black men as combat pilots and support personnel proved a massive success.

Fighting discrimination at home to ensure freedoms overseas

While slavery in the US was officially abolished in 1865, segregation and racism became the norm, especially in the deep South – the states that had depended the most on the enslavement of black men, women and children who were bought, sold and exploited.

The US military at the time was also segregated.

An Army War College Report written in 1925 entitled The Use of Negro Manpower in War only served to reinforce this discrimination, stating: "The Negro is by nature subservient and believes himself to be inferior to the white man.

"He cannot control himself in the face of danger to the extent the white man can.

"He is mentally inferior to the white man."

The report had a significant impact on the way black men and women were treated within the US military and this discrimination continued until the implementation of the Tuskegee Experience in 1941 and its eventual success.

Despite black people proving their worth in every major American conflict since its independence from Great Britain, during the Second World War, they were offered roles behind the frontline such as drivers, maintenance and catering.

A change in the law on 16 September 1940 to ensure the US had enough military force in case it had to enter the Second World War – the first peacetime draft in United States history – finally gave black men the chance to fight for their country.

The War Department announced that the Civil Aeronautics Authority would join forces with the US Army to train "coloured personnel" for the aviation service.

The pioneering Tuskegee Airmen

And so, intense training began for the men who would later become some of the best pilots in the US Army Air Force (the predecessor of the US Air Force), with an impressive 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses between them.

Tuskegee, Alabama, was selected to train black military pilots because the city was already training black civilian pilots.

This was thanks to President Roosevelt asking Congress on 12 January 1939 to pass legislation to authorise a permanent civilian pilot training programme that would not exclude anyone because of their race.

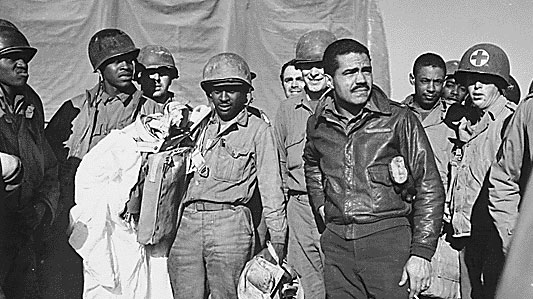

The first class of 13 military aviation cadets began their primary training on 19 July 1941 and, by March 1942, five of the original cadets had graduated, one of whom was Benjamin O Davis Jr.

The skilled pilot became the most famous commander of the Tuskegee Airmen and would later become the first black general in the US Air Force, receiving a fourth star after his retirement.

Another first was the formation of 99th Pursuit Squadron from the Tuskegee-trained pilots – the first black flying unit in American military history.

Later known as the 99th Fighter Squadron, it was without pilots for a year while the men were being trained.

Of the 932 who completed flight training at Tuskegee Army Airfield, 355 flew in Europe during the Second World War.

These pioneers who would eventually blaze a trail through war-torn skies over Europe, became known as Tuskegee Airmen, no matter which squadron they were assigned to because of where they trained.

The Father of Black Aviation and the First Lady

In the 1930s, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt spoke openly about her desire for racial equality.

Despite being threatened by the Ku Klux Klan, the white supremacist terrorist group, she remained undeterred from her mission to reunite segregated America.

While visiting the Tuskegee Institute's Moton Airfield in 1941, Mrs Roosevelt met self-taught pilot 'Chief' Charles Alfred Anderson – a man who would become crucial in breaking the racial barrier for black pilots.

In a video made by the Pare Lorentz Center at the Franklin D Roosevelt Presidential Library, Mr Anderson speaks of the moment he spoke with the First Lady just before he made history by being the first black pilot to fly a president's wife.

He reported her as saying: "I always heard that coloured people couldn't fly airplanes, but I see you flying all around here."

An iconic photo was taken of the historic moment that, just like the photo of Princess Diana walking through a minefield helped boost the campaign for a global landmine treaty, helped bring the fight for racial equality to the forefront of people's minds.

It also helped convince the First Lady's husband, President Franklin D Roosevelt, to send the Tuskegee Airmen to North Africa in April 1943 and then Europe.

The Red Tails: A lick of paint and a nickname was born

The first black American military pilot to shoot down an enemy aircraft – a Luftwaffe Focke-Wulf Fw 190 – in combat was First Lieutenant Charles B Hall of 99th Fighter Squadron on 2 June 1943.

The skilled pilot was flying a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighter-bomber aircraft, known by the Royal Air Force as Tomahawks or Kittyhawks and easily identifiable by the shark mouth painted on the nose.

And it was paint that led to the creation of the Tuskegee Airmen's first nickname – The Red Tails.

While under the command of Colonel Benjamin O. Davis in 1944, the 332nd Fighter Group were assigned to fly escort missions for bombers of the 15th Air Force and were given the aircraft Republic P-47 Thunderbolt.

To distinguish themselves from other fighter aircrafts, the pilots painted the tails of their P-47's in red paint, a tradition they continued with all future aircraft – such as the P-51 Mustang fighter-bomber they became famous for flying – until they were disbanded in 1946.

Due to the Tuskegee Airmen's proficient skills in the skies while escorting and protecting bombers deep into enemy territory, the men became known as the Red-Tail Angels by the exclusively white piloted bomber crews they escorted.

By their determination for excellence and success in exceeding all expectations, the Tuskegee Airmen impressed many of their white counterparts.

George Lucas' passion for celebrating the Tuskegee Airmen

In 1988, George Lucas, the iconic American film-maker partly responsible for the massively successful Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises, decided he wanted to shine a spotlight on the Tuskegee Airmen and their vital contribution to the civil rights movement and the Allied success over Nazi Germany.

However, he faced obstacles at every stage, and it wasn't until 2012 and a considerable investment of his own money – $58m into making the movie and $35m for its distribution – that the film Red Tails was released.

Starring David Oyelowo (Selma), Cuba Gooding Jr (Pearl Harbor) and Terrence Howard (Empire), Red Tails sparked awareness of the extraordinary success of pilots and ground crews who had to fight for their right to serve their country.

Speaking in 2012 with NPR journalist Michel Martin, David Oyelowo who played fighter pilot Joe 'Lightning' Little, spoke of the men and what they achieved, saying: "They overcame these adversities with excellence.

"They didn't spend their whole time carping about the inequities that they were suffering, they just were excellent at what they did and, with time, Truman, the rest of the country had to acknowledge them.

"That led to the desegregation of the military, which led to the desegregation of the South, which led to the civil rights movement, which led to us now having a country in which we can have an African-American president."

Paving the way for desegregation

The pioneering men and women of the Tuskegee Experience proved they were not inferior, less intelligent or cowards. They were a courageous, bright and history-making group of people.

As the first black pilots in American military history, their historical significance cannot be denied.

By showing their excellence in aerial combat, they paved the way for future black men and women to see that they deserved the same opportunities afforded to white service personnel.

While they fought for the freedoms of others in Europe, they faced vile discrimination at home – a country they were fighting for.

Their glowing record encouraged the US Air Force (officially formed in 1947 from the US Army Air Corps) to integrate before the other services so many Tuskegee pilots and ground crew who wanted to continue their military career stayed with USAF post-war.

During an interview with Forces News in 2023, retired US Army Colonel Edna Cummings discussed the 6888th Battalion – a group of predominantly black US Army women whose proficiency in sorting missing post was vital in boosting morale during the Second World War.

However, just like the Tuskegee Airmen, their efforts were overlooked in the US.

Col (Ret'd) Cummings highlighted that these women, the men from Tuskegee and many more played a key role in leading the way for desegregation after the end of the war.

She said: "In 1948, President Truman was made aware of how these black veterans were being treated and the blinding of Isaac Woodard prompted him to do three things."

Following the violent beating of black soldier Mr Woodard upon his return from war, President Truman set into law three important pieces of legislation.

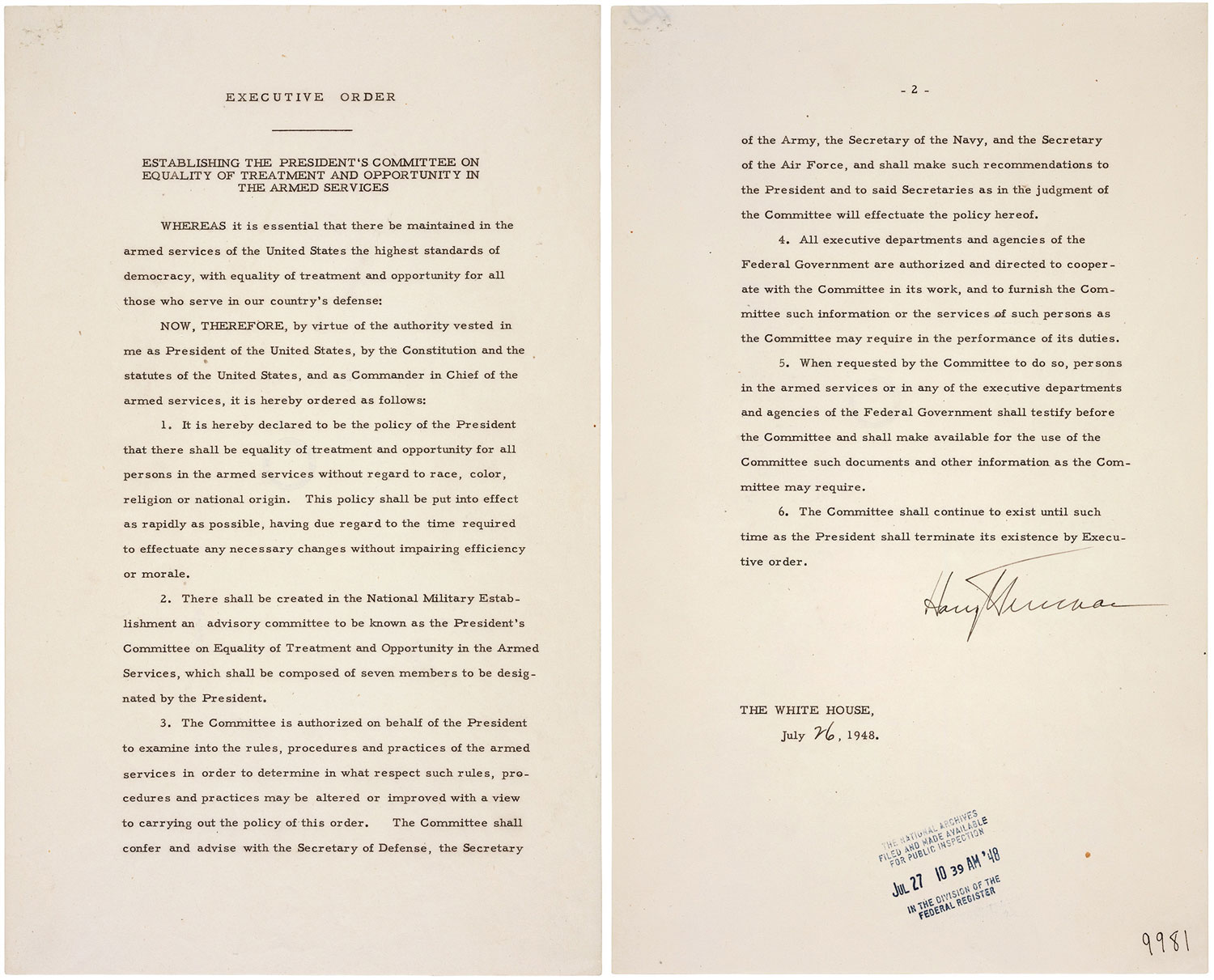

One of which was the desegregation of the US armed forces in July of the same year.

Col (Ret'd) Cummings said: "You have the Six Triple Eight, the 320th Balloon Barrage Brigade, the Red Ball Express, the Tuskegee Airmen, the Montford Point Marines, and all of these black units who proved that if given the training and opportunity – the operative term is 'opportunity'... you can see they perform with their peers and some exceeded what was expected of them."

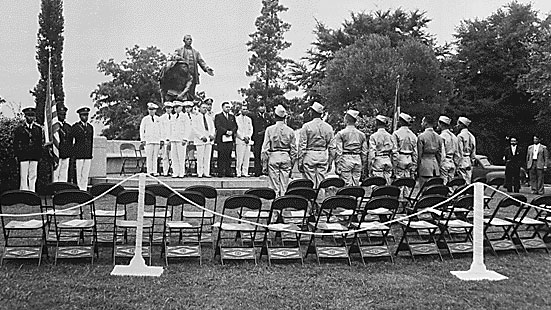

On 29 March 2007, President George W Bush and Nancy Pelosi, former Speaker of the House of Representatives, awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the Tuskegee Airmen for their "outstanding combat record [that] inspired revolutionary reform in the armed forces".

At the service attended by about 300 surviving Tuskegee Airmen, the president told the men: "I would like to offer a gesture to help atone for all the unreturned salutes and unforgivable indignities.

"And so, on behalf of the office I hold, and a country that honours you, I salute you for the service to the United States of America."