100 Years On: Oppy Wood Horrors Revealed In Survivor's Letter

On May 3, 1926 - exactly nine years after the carnage of Oppy Wood - a survivor offered a personal account of the battle.

His letter was published in the Hull Daily Mail.

Now, 100 years on from the battle that left nearly 300 Hull Pals dead, the letter has been published again:

"In the course of business the other day I made an appointment for May 3rd and the very fact of typing that date awoke some chord in my memory.

It is a strange fact that during the war one felt things were so impressed upon one's memory as to be unforgettable, and yet, though the date was familiar, I had to pause to fix its real association.

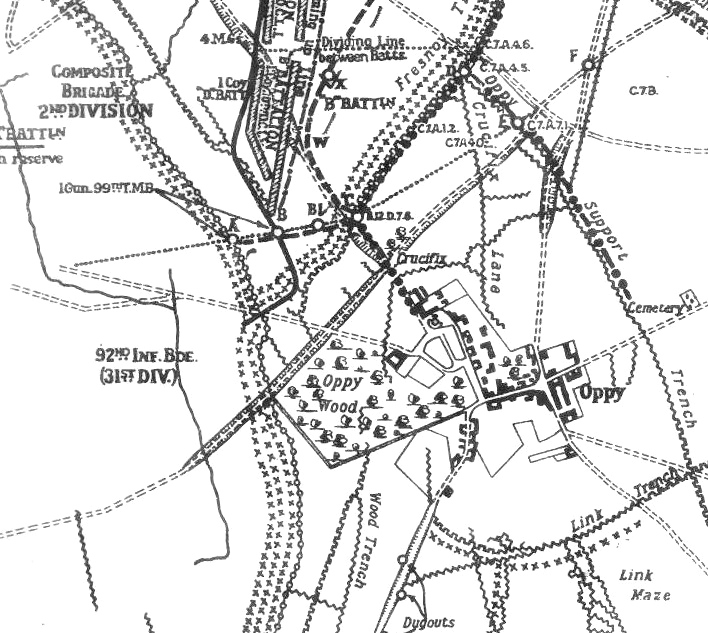

We were there four days, doing nothing in particular, and I suppose being held in reserve for the attack on Oppy.

On the night of May 2nd, in fighting order and prepared for the worst, we moved up to the front.

It was a fine moonlight night, and as the front was new to us and the stupendous feat of the Canadians in taking the Ridge still fresh in our minds, we found enough to interest us in our surroundings.

We were marching in column of route over a flat moonlit plain when a salvo of shells bursting amongst us suddenly scattered us.

I was attached to a Lewis gun team and we occupied adjacent shell-holes and deepened them for protection.

As soon as I felt safe I fell asleep. I awoke to the sound of renewed shelling and found another occupant in my shell-hole.

It was Captain Reeve, and he was as cool as though it was merely a field day.

He was annoyed because "B" Company, or rather some members of that valiant company, in moving about had drawn the enemy artillery fire.

I gathered that it was within a minute or two of zero and Captain Reeve feared that the movement would make the enemy suspicious.

Then hell broke loose, and in response to the call of the team commander I staggered out of the shell hole and ran across the broken ground. It was dark and a heavy pall of smoke hung around.

Moreover, I am not what is popularly known as built for speed, and, handicapped with panniers of ammunition and the rest of infantry kit, I was soon outdistanced.

I knew shells were dropping round about simply by the sudden eruption of the ground close by.

The noise was too great for single explosions to be heard. I ran on hopefully and soon became conscious that it was getting light very quickly.

After a few minutes, I came up to some of the battalion and was told to lie down and keep still.

I obeyed the injunction and flung myself down, glad of the respite.

A chap close to me told me that the attack was a hopeless failure, and then I became conscious of a disagreeable smell.

I soon discovered that I was on a dead Englishman and from all appearance, a shrapnel shell had burst just above him. At any rate, his haversack, head and shoulders, and steel helmet bore marks that would correspond to such an occurrence.

So I hastily wriggled to a part of the trench that was about two feet deep, and from that position surveyed the front.

By this time it was full daylight and the shelling had stopped.

Slightly to my left, the ill-fated wood splintered, but still distinctly a wood, showed clear and distinct.

To my right front, a few figures in grey moved about unconcernedly, searching the ground somewhat after the fashion of children looking in the pools at the seaside after the tide has gone down.

I saw one group make a beckoning movement and then three khaki figures got up and moved away with them – prisoners.

No one in our trench attempted to fire and we were passionless spectators of a scene that was, to me at least, dangerously near farce.

I looked behind me where the Ridge swept upwards, and on the top, I saw a column of smoke riding steady and straight into the clear air and I thought enviously of somebody's cooker preparing somebody's breakfast.

A message was passed down the left to the effect that we were to move out towards our left sent me crawling down the narrow trench to a wider spot.

I also found that it grew deeper and I found a part with a kind of seat and quite good cover.

The only drawback was that about six feet from me, and facing me, was a dead British soldier.

He looked as though he was asleep, with his head resting on the side of the trench, his eyes closed, and with just a thin trickle of dried blood from the corner of his mouth.

I imagined he had been killed by the concussion from a shell exploding because he was buried up to his waist and appeared otherwise unhurt.

I thought of his relatives and wondered if they knew.

It was too dangerous to move him, so I resigned myself to his quiet company for the rest of the day.

The day seemed an eternity. It was a perfect May day and the sunshine beautifully, but in the immediate vicinity of Oppy Wood, no one felt equal to Nature study.

On the whole, the day was quiet, as though both sides desired to rest after their exertions at dawn.

There was very little rifle fire and the only excitement so far as I was concerned was a shell that burst about five yards from the trench.

I do not know whether it was one of theirs or one of ours.

So morning lengthened into the afternoon and afternoon faded into evening, and when it was dark the first officer I had seen all day came up and ordered us to deepen the trench.

I asked him what we had to do with the dead man, and he said:

"Oh, turn him out as well; he'll help to make the parapet."

Callous? – oh, well, that's war, and you cannot consider finesse when men's lives hang in the balance.

Unfortunately, the moon rose again and the constant ping of machine gun bullets indicated plainly enough that the Germans guessed pretty well what we were doing.

To work was a relief, and it brought me into contact with my brothers in misfortune, and I heard we were being relieved.

For once the rumour was right, and we went out in small bodies and as quietly and unobtrusively as possible,

because in war you think of the chap who is relieving you and you neither want him shelling nor yourself.

The progression for the first half mile was painfully slow.

The German artillery were dropping casual shells all over the plain and the German machine gunners were instilling caution by bursts of sweeping bullets.

So from one shell hole to another in short bursts, stooping low and breathing hard, I reached a sunken road, dead weary and heartily fed up.

Here the remnants congregated and at length started on the nightmare march out.

Walking almost asleep and unconscious of anything beyond the desire to get out of danger, and sleep, we trudged along in silence.

At length we reached out billets and over tea and rations munificent, because of our lessened numbers, the day's happenings were pierced together.

I heard of the gallantry and death of Jack Harrison; of the death of Captain Reeve; of this one killed and that one wounded; of Tom's adventures and how Harry had fared; and then to sleep. And that same night we went back into the line.

Any ex-soldier reading this will understand."