Life In A German Camp: Diary Of British WW1 Captive Comes To Light After A Century

Cover: SWNS.

The diary of a British WWI captive, which describes the emotional toll of life in a German internment camp, has come to light after 100 years.

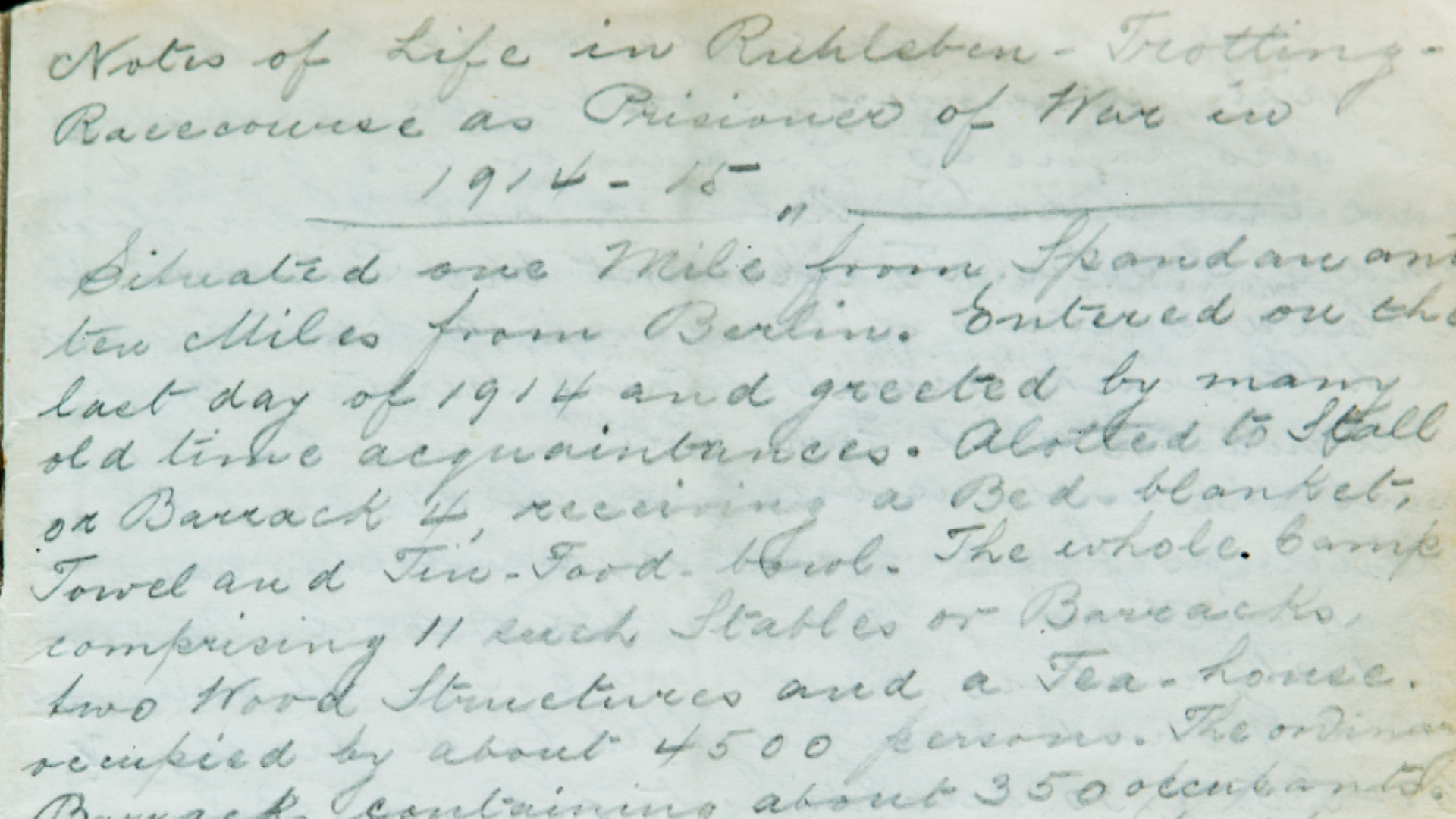

Albert Stockwell documented his stint spent as a prisoner in poor conditions at Ruhleben camp at Spandau, Berlin, following the outbreak of the war.

The civilian, from Stanningley, West Yorkshire, was working in a textiles factory in the town of Wittenberg, Germany when the war began in 1914.

The then-49-year-old was forced to uproot and move into the camp to prevent him returning home to England and being conscripted because he was of fighting age.

His wife Mary and son Harry sought visas to return to the UK which they were given, but the boy, who was a 14-year-old electrician apprentice, was told by his employer he could not leave.

Dramatically, the pair hid on a train and managed to get a ferry back to Britain.

Albert's diary describes every aspect of camp life, from daily chores and morale-boosting cricket leagues to the death of his infant son in England and the tragic suicide attempts of fellow detainees.

One particularly poignant entry, dated 6 May 1915, reads: “Being in captivity as we unfortunately are, the wonders of nature have never before so strikingly appealed to us.

“The budding and breaking into leaf of the numerous trees in our midst, vegetation life, the sweet singing of the birds all tend to sharpen our longing for freedom.”

Albert was eventually allowed to return home in 1916 due to advancing years and failing health - although was described as a "broken man" by his great-grandson Paul Driver, 68.

Mr Driver said: "I was doing family research and came across it again after not seeing it for many years.

"I thought it was interesting enough for it to be put on display.

"There are a lot of history books around but this one was very personal and he was from the area so I thought it made sense."

He recalled the incredible story of his grandfather, Harry, and great-grandmother's escape from Germany:

"They were all set to leave when my grandfather was told by his employer he wouldn't be allowed to. So they both hid on a train to flushing port where they got the ferry back over.

"My grandfather had lived in Germany for his whole life at that stage and spoke no English.

"When he came across he had to pretend to be a refugee as he only spoke German. He learned English by reading comic strips."

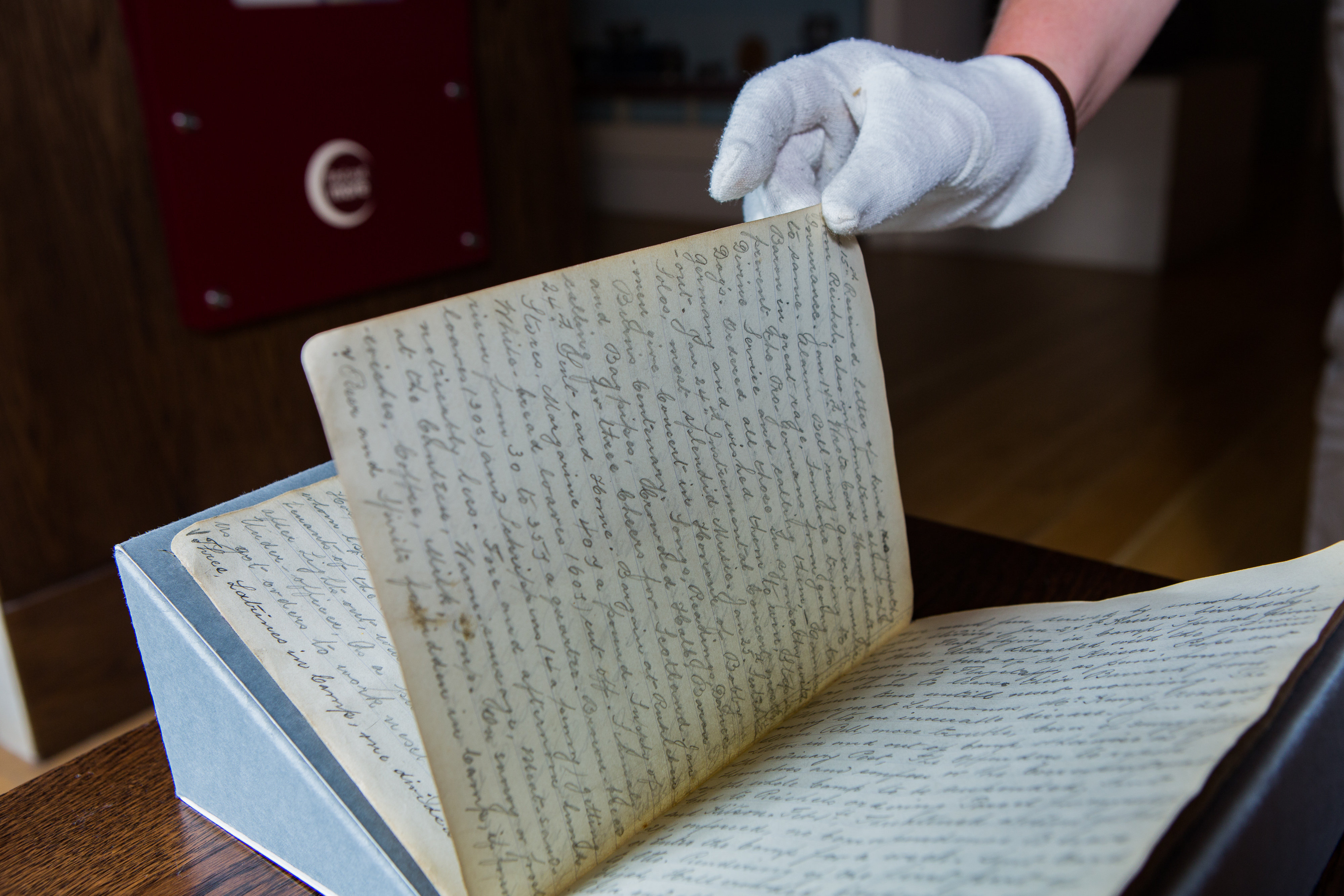

Albert's moving entries are being shown to the public for the first time as part of a display focusing on the thousands of civilians based abroad whose lives were turned upside down by the outbreak of war.

The museum’s Preservative Party, a group of young curators, researched the diary, which also features a selection of images and objects exploring an often forgotten facet of wartime history.

Lucy Moore, project curator with Leeds Museums and Galleries, said: “Albert goes into an extraordinary amount of detail about his time at Ruhleben.

“Reading his diary, it’s impossible not to empathise with him and his fellow detainees and realise the huge emotional toll internment must have taken on them all.

“Abruptly wrenched away from the lives they had built abroad and faced with a very uncertain future, these men displayed incredible resilience and courage.

“Thanks to people like Albert, who eloquently articulated their thoughts, emotions and experiences more than a century ago, we have been able to better understand and commemorate their legacy as we also celebrate their story.”