On This Day: Evesham - The Battle That Changed English Politics For Good

Click left for part one of this story.

It is 1265 and England is on the brink of a political revolution.

The previous year, King Henry III and his son Edward were bested at Lewes by the rebellious baron Simon de Montfort.

Now, de Montfort and his baronial allies rule England in the captive king’s name.

That was the scorecard at the end of 1264, at any rate. But while Henry had been reduced to little more than a puppet, Simon struggled to convert his triumphant military victory into a lasting political one.

He made a few failed stabs at forming a parliament, first in June 1264, and then again the following January.

The 1265 parliament was unique in that it contained not only England’s nobles, but representatives from important towns – a House of Commons in the making.

Yet, popularity with the common man and lower gentry wasn’t enough to compensate for a lack of it with the nobles.

One of these was the young Gilbert de Clare, the Earl of Gloucester. He’d been angered at first by the King, who denied his inherence on account of him not being 21. Though he soon became disillusioned with de Montfort, and when Simon intervened to prevent a tournament (he saw them as ‘nurseries of discord’) between him and Henry de Montfort, Gloucester switched sides.

When Prince Edward managed to escape his guards and join him, the scene was set for another showdown.

The Battle

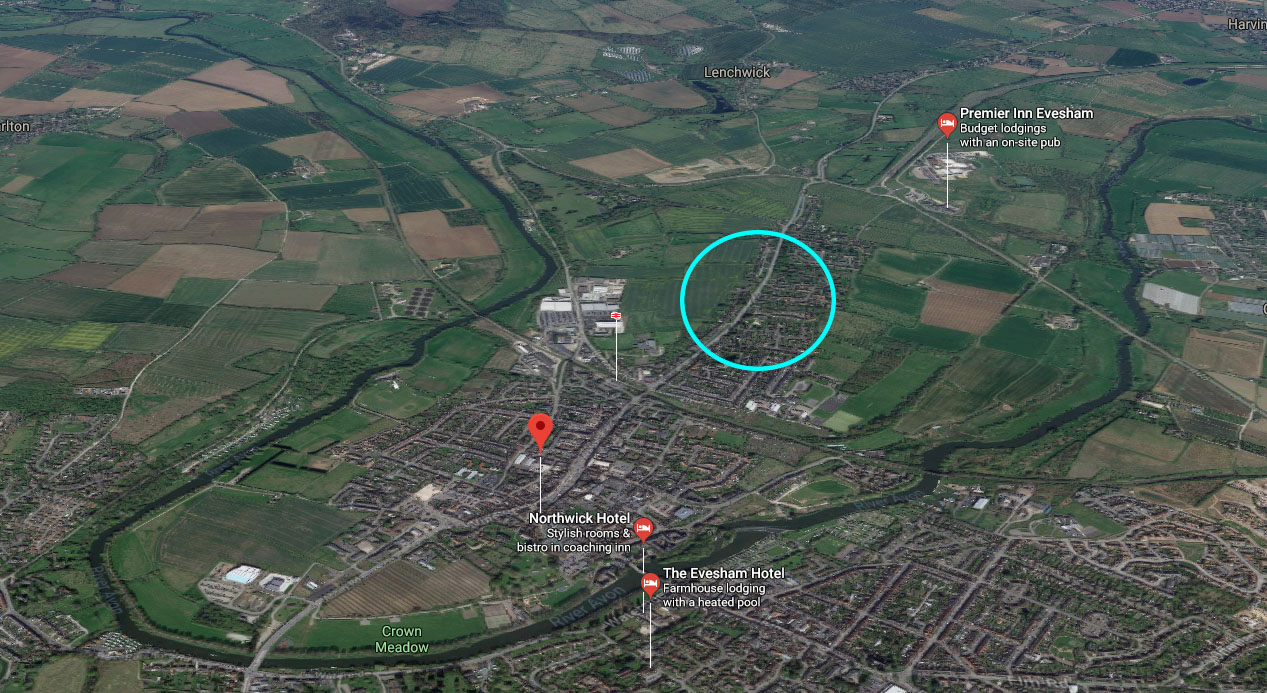

On the morning of 4th August, de Montfort awoke to news that Royalist troops were gathered on Greenhill, Evesham, ready for battle.

Quickly mustering his troops, de Montfort rode out to meet them, standard proudly displayed.

From the offset, the Royalists were at an advantage, outnumbering de Montfort’s men 3:1. Edward chose to conceal most of his force and make a portion of it visible to draw the rebels out.

Thirsty for revenge on his ‘upstart’ former captors, Edward attacked without mercy.

It was the norm for the peasant foot soldiers to bear the brunt of a medieval battle – knights preferring instead to capture and ransom fellow knights. But this time would be different.

Henry de Montfort was “cleft in two with a sword” in front of his father’s eyes, and Simon de Montfort himself had his horse “cut from under him by infantrymen”.

Such was the chaos of the battle that King Henry himself - brought along in Simon’s train - became an accidental target of Royalist savagery. He reputedly had to yell:

“I am Henry of Winchester, your king - do not kill me!”

It was only by chance that he escaped at all; wounded in the shoulder by a javelin, he was eventually recognised and escorted to safety by one of Edward’s knights.

Despite the carnage, Simon held out without his horse and, according to the period chronicler known as Oxnead, was:

“…bravely fighting against the infantry, defending himself until his enemies dismounted from their horses, basely took him from behind, stripped him of his armour, and thus naked killed him…with his last breath (de Montfort) said “Dieu merci” and so gave up his life”.

De Montfort’s killing is a contentious issue; many claim that he was killed in Edward’s absence and against his will. He was, according to the account of 13th-century monk Wykes, “struck through the neck with a lance”.

Whatever the case, once he was dead, de Montfort’s body was savagely mutilated.

In fact, so total was the devastation caused by Edward’s army that one of his contemporaries, the historian Robert of Gloucester, described it as “a murder of Evesham for battle it was none”.

The last of de Montfort’s knights were eventually overcome next to a spring, later dubbed Battle Well.

Soon afterwards, stories of miracles taking place around the well began to circulate. Said to be a source of healing, people made pilgrimages there, and the site became so popular that a small chapel was built in memory of those who had died at Evesham.

The battle itself was short lived. Accounts written by monks suggest that it was over within two hours, with baronial casualties estimated to be around 4,000 - almost 80 percent of their whole force.

Although the Second Barons’ War would drag on, victory of the Royalist forces at Evesham and the death of de Montfort dashed any real hope of a baronial victory in the conflict.

As Richard Brooks points out in his book ‘Lewes and Evesham’, the fact that the Royalist side did win most likely prevented England from becoming a series of separate states headed by different nobles, like Germany before its unification in 1871.

However, even if Evesham did restore royal authority in the near term (Edward was crowned King seven years afterwards), in a way, de Montfort won the long game. Lewes and Evesham had an enormous impact on the way in which the crown and Parliament functioned - the reforms introduced by de Montfort in many instances became law, giving England a more just medieval system of central government and contributing to the beginnings of our modern democracy.

For more, read ‘Lewes and Evesham 1264-65: Simon de Montfort and the Barons’ War’ by Richard Brooks and visit Osprey Publishing for more titles.

Additionally, visit Karwansaray Publishers for more great titles, and read their volume ‘Medieval Warfare’ for a rich pictorial approach to military history.