Exclusive: Inside the Ukrainian ketamine clinic treating soldiers suffering with PTSD

By Hannah King in Ukraine

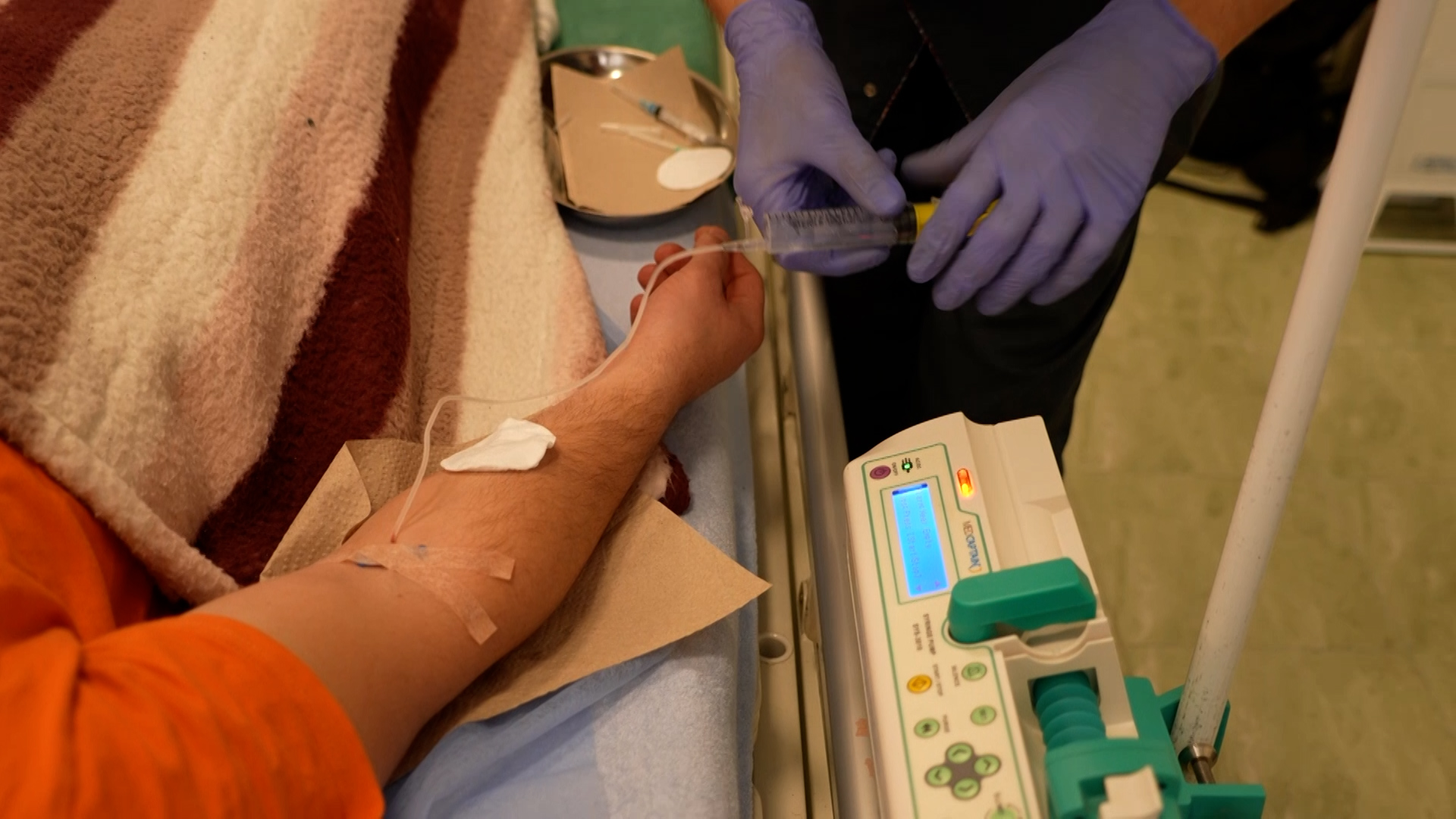

In a private clinic on the top floor of a dreary children's hospital in Northern Kyiv, 31-year-old Taras lies with a needle in his arm, delivering a clear fluid into his veins, as a therapist armed with paper and pen talks to him in the softest of tones.

Taras is a children's music teacher. He went to fight on the frontline, but after two weeks he had a panic attack and had to return home.

The drug he is being given is not new and it is not illegal when given medically, but it is not traditionally used to treat mental health.

It is ketamine, a licensed anaesthetic drug, but not a treatment that has been medically approved for psychiatry, either in Ukraine or in the UK, although in the UK certain NHS trusts do provide a paid-for service to use it to treat depression.

Clinicians in Ukraine, however, have found ketamine-assisted psychotherapy to be hugely effective in treating the likes of anxiety, PTSD and depression, particularly in its rapidly growing population of veterans.

Dr Vladislav Matrenitsky, the psychedelic therapist who runs the clinic, says about a third of his ketamine patients have "extremely good" results, and another third "reasonably good" ones.

Bad reactions, usually panic attacks, are rare, and the ketamine drip is stopped immediately if they happen. He has treated hundreds of patients since the start of the war, and a growing number of them are military.

But those who come do so unofficially.

Whilst in military service they are not allowed to seek private therapy and must be treated by state military hospitals where ketamine treatment is not available.

Dr Matrenitsky is currently lobbying the government to change this.

He also wants them to declassify psychedelic drugs like MDMA, the active ingredient in ecstasy, and psilocybin (magic mushrooms).

These drugs are currently illegal but show great promise for use in psychiatry. Declassification would allow more research to be done into their use for treating conditions like PTSD.

This is something some researchers in the UK and around the world have been arguing for for years.

In 2023, Australia became the first country to allow MDMA and psilocybin drugs to be used in medicine. Other countries will likely follow suit.

Progress, however, feels slow and researchers are increasingly frustrated, finding themselves caught in a cycle where governments demand more evidence before declassification, but the illegal status of psychedelic drugs seriously restricts research being done.

But war can often accelerate change.

Ukraine faces a mental health crisis. A study published in The Lancet medical journal predicts that more than half the population may already have PTSD.

Given the mental health catastrophe they face, Dr Matrenitsky feels they are close to big changes in legislation in Ukraine.

He hopes that within a year they will at least have permission for clinical research into the use of MDMA and psilocybin.

Ukraine's drug enforcement agency says it isn't averse to rescheduling psilocybin and MDMA in a medical context, although the Minister of Health has requested more clinical data.

A local pharmaceutical company has offered to make MDMA for the equivalent of £8 per dose, far less than it costs in the UK or the US, so that small Ukrainian trials may begin.

"There is nothing else at the moment from traditional medicine that is as efficient as psychedelic drugs. That is why it is considered to be the medicine of the future," says Dr Matrenitsky.

"Actually the need is very high because American research shows that veterans respond to standard therapy even less than the average civilian population.

"So we may expect at the end of the war that we will have many veterans who are hardly treated. We need to be prepared."

Dr Matrenitsky says ketamine-assisted psychotherapy can work 10 times faster than existing treatments.

Each 40-minute session costs the equivalent of just over £75, although they do try to provide a small number of treatments free to soldiers where possible. A typical course consists of two to six sessions.

Ukrainian politicians seem largely supportive of change.

Forest Glade, a government military rehabilitation centre, sponsored a conference this year on psychedelics in psychotherapy.

But the centre's director, Kseniya Vozsnityna, thinks psychedelics should be used sparingly, and never for active soldiers, saying: "This is a therapy for difficult situations, medication-resistant PTSD when the usual methods don't work."

There is still stigma and uncertainty within society around using drugs like ketamine, MDMA and psilocybin. But what seems radical now, may be normal tomorrow, especially when accelerated by war.

"It's known from the history of medicine, in the beginning, it's something bad, something awful, you shouldn't use it," says Dr Matrenitsky.

"Then people say, okay perhaps this sounds interesting, but in the third step, everybody knows it. And they say why? – why don't you use it? Most important – is when personal experience spreads."

As for Taras, he says the ketamine has transformed his life.

"I hated the life I had before because it's terrible when you have depression and no one can help you."

"I really believe and hope, in a year, that our government might have a lot of clinics for military people. A lot of my friends come back and their mental health is really low. And I'm afraid."

These drugs can, of course, be dangerous when not used clinically and more research is needed – something Dr Matrenitsky is constantly looking for help to fund.

But with supportive legislation, progress can be made and psychiatry in Ukraine may begin to inform the world.