Sidney Bates: Hero who charged enemy head-on with a machine gun, earning him Victoria Cross

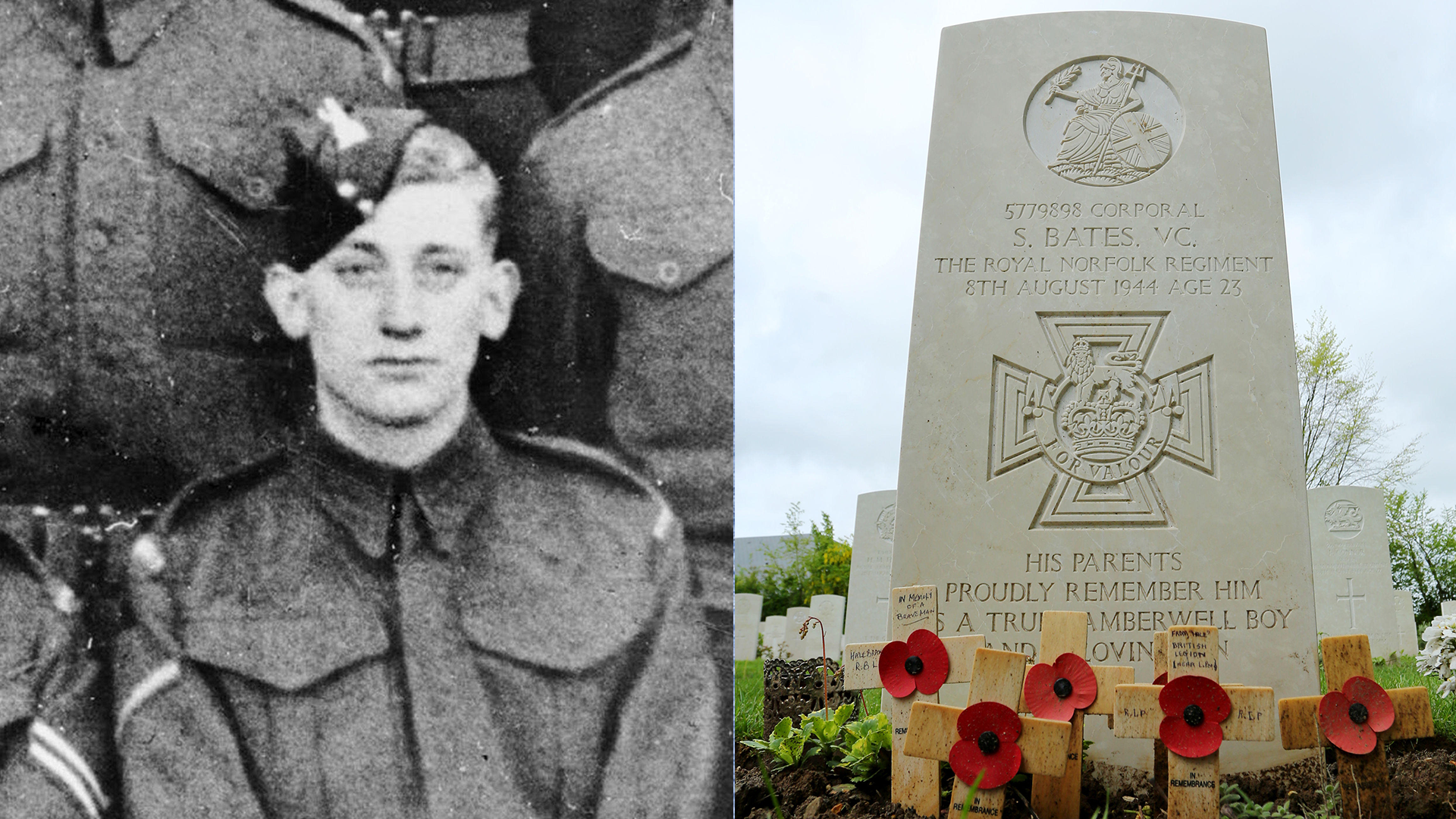

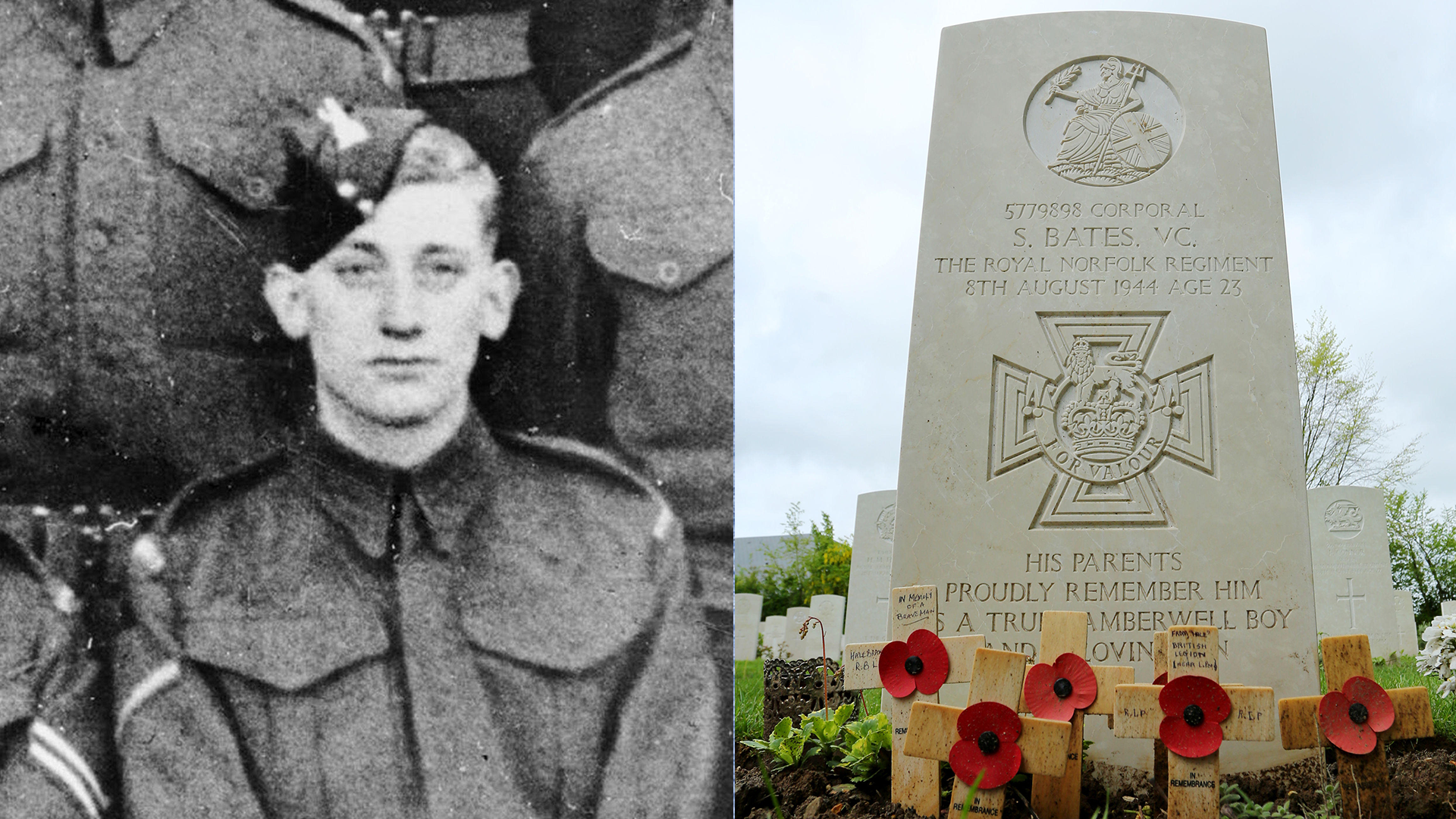

Among the many graves in Normandy is that of Corporal Sidney Bates, the only Victoria Cross holder on the British Normandy Memorial.

Cpl Bates was posthumously awarded with Britain's highest military honour for facing Waffen-SS panzergrenadiers head-on with a machine gun.

Despite overwhelming odds, the 23-year-old soldier held his ground, charging through a hail of bullets at the enemy.

- Last living Gurkha recipient of Victoria Cross dies at the age of 83

- Operation Pluto as told by a D-Day veteran

- D-Day: The veteran who volunteered aged 17 'to avenge his brother's death at Dunkirk’

Inspired his troops until the last bullet

Born on 14 June 1921, in Camberwell, south London, Sidney grew up in a working-class family.

The son of Frederick Bates and Gladys May (nee Doughty), the future VC recipient worked as a carpenter's labourer before joining the Army at the outbreak of the Second World War.

He joined the 1st Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment in June 1940, shortly after it returned from Delhi and rose to the rank of corporal.

During the Battle of Normandy, Cpl Bates, known to his comrades as Basher, was the section commander among British infantry under attack by 50 to 60 elite members of an SS Panzer Corps.

The Panzer Corps was the main strike force of the Wehrmacht, responsible for many of Germany's earlier battle victories.

With 4,415 Allied personnel killed on 6 June alone, maintaining ground and gaining momentum after D-Day was paramount to ensuring the success of Operation Overlord.

After a Bren gunner had been killed next to Cpl Bates, he immediately grabbed the machine gun from his fallen comrade, leaving the the safety of his slip trench, and charged at the enemy.

Despite being gravely wounded, Cpl Bates continued his relentless assault until he collapsed from his injuries.

He repelled the enemy attack and secured the position, inspiring his company to keep fighting. Despite being outnumbered, the British held the position, with the Artillery seeing the enemy off.

Tragically, Cpl Bates succumbed to his wounds on 8 August 1944, at the age of 23.

The recommendation for the Victoria Cross was made by Major Cooper-Key, the commanding officer of B Company of the 1st Battalion. Initially the proposal was turned down but Maj Cooper-Key persevered.

Since its inception in 1856, there have been 1,358 Victoria Crosses awarded, with 181 awarded during the Second World War.

Cpl Bates is buried in the Bayeux Commonwealth War Graves Commission War Cemetery. His Victoria Cross is displayed at The Royal Norfolk Regiment Museum, Norwich, having been purchased by the Royal Norfolk Regiment in the 1980s for £20,000.

'Supreme gallantry and self sacrifice'

Cpl Bates' act of valour is best captured in the official citation for his Victoria Cross.

Published in the London Gazette on 2 November 1945, the War Office citation reads: "The King has been graciously pleased to approve the posthumous awards of the Victoria Cross to Corporal Sidney Bates, The-Royal Norfolk Regiment.

"In North-West Europe on 6th August, 1944, the position held by a battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment near Sourdeval was attacked in strength by 10th SS Panzer Division.

"The attack started with a heavy and accurate artillery and mortar programme on the position which the enemy had, by this time, pin-pointed. Half an hour later the main attack developed and heavy machine-gun and mortar fire was concentrated on the point of junction of the two forward companies.

"Corporal Bates was commanding the right forward section of the left forward company which suffered some casualties, so he decided to move the remnants of his section to an alternative position whence he appreciated he could better counter the enemy thrust.

"However, the enemy wedge grew still deeper, until there were about 50 to 60 Germans, supported by machine guns and mortars, in the area occupied by the section.

"Seeing that the situation was becoming desperate, Corporal Bates then seized a light machine-gun and charged the enemy, moving forward through a hail of bullets and splinters and firing the gun from his hip.

"He was almost immediately wounded by machine-gun fire and fell to the ground, but recovered himself quickly, got up and continued advancing towards the enemy, spraying bullets from his gun as he went.

"His action by now was having an effect on the enemy riflemen and machine gunners but mortar bombs continued to fall all around him.

"He was then hit for the second time and much more seriously and painfully wounded. However, undaunted, he staggered once more to his feet and continued towards the enemy who were now seemingly nonplussed by their inability to check him.

"His constant firing continued until the enemy started to withdraw before him. At this moment, he was hit for the third time by mortar bomb splinters, a wound that was to prove mortal.

"He again fell to the ground but continued to fire his weapon until his strength failed him. This was not, however, until the enemy had withdrawn and the situation in this locality had been restored.

"Corporal Bates died shortly afterwards of the wounds he had received, but, by his supreme gallantry and self sacrifice he had personally restored what had been a critical situation."

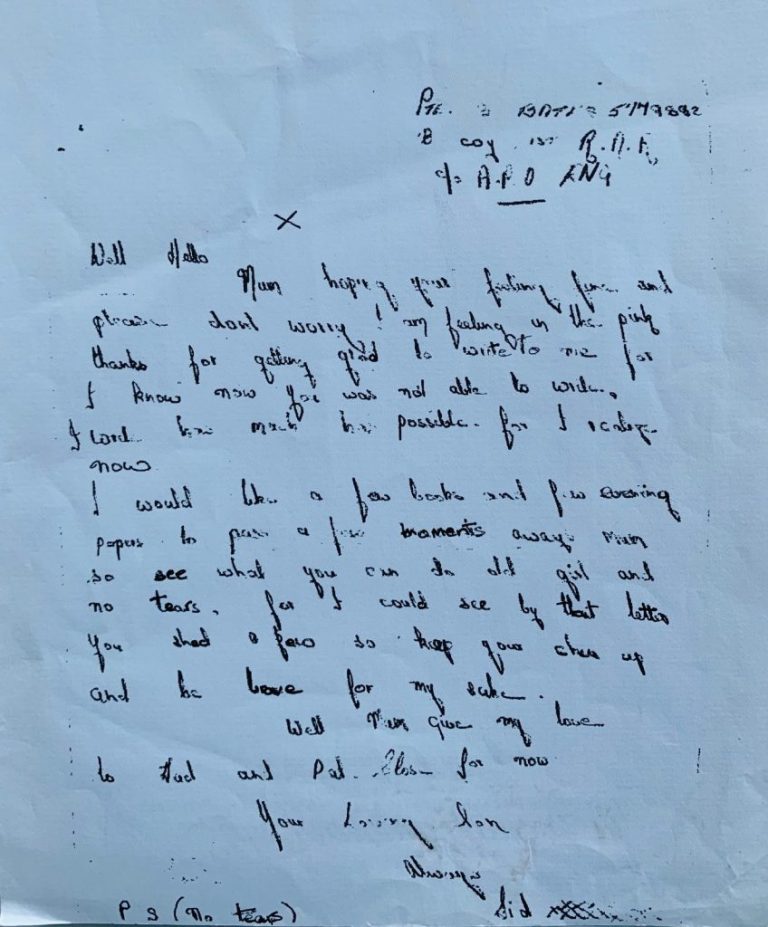

Sidney's last letter home

Cpl Bates, the only Victoria Cross recipient named on the British Normandy Memorial, is remembered not just for his extraordinary bravery but also for the kind of caring and fun-loving person that he was.

Brought up in a small terraced house in Councillor Street, Camberwell, he occasionally helped his father, a rag and bone man, sell tarry blocks – discarded wood covered in tar that poor families would use to heat their homes.

One of four brothers, Sidney was a practical joker with a dry sense of humour.

He was very protective of his younger brother Bert, the two of them being nearly inseparable.

Tall, blonde, and athletically built, Sidney caught the eye of many girls, but he remained faithful to his girlfriend Jean, whom he had known since he was nine.

Cpl Bates was close to his family, especially his mother Gladys May who received his final letter.

A transcript of the letter is as follows:

"Well hello Mum

"Hoping your feeling fine and please don't worry, I am feeling in the pink.

"Thanks for getting Glad [Sid's eldest sister] to write to me as I know now you was not able to write. I write as much as possible for I realise now.

"I would like a few books and few evening papers to pass a few moments away, mum, so see what you can do old girl and no tears for I could see by that letter you shed a few so keep your chin up and be brave for my sake.

"Well mum, give my love to Glad and Pat [Sidney's youngest sister]. Close for now

Your loving son

Always

Sid

(P.S. No tears)"

Cpl Bates' story is one among many, a reminder of the self-sacrifice at the heart of victory and the young lives lost to give us the freedoms we know today.