Britain's nuclear bomb guinea pigs: The untold story

As war rages in Ukraine, the idea of nuclear attack rears its ugly head once again.

Today, Britain relies on collaboration with her allies together with her own nuclear deterrent to protect against attack.

But how did it all begin?

In a special report, we hear from three men who helped test Britain's very first nuclear capability.

"I'm sure we were Guinea pigs. That's why we were all there exposed…I think we were part of the experiment. It seems a bit primitive now but I guess it was the best way to find out." Dick Bridges, former national serviceman.

How did we get here?

During the Second World War, Britain worked on the US-led Manhattan Project, directed by nuclear physicist J Robert Oppenheimer, to develop the world's first atomic bomb.

The Unites States' spending on the endeavour dwarfed the UK's.

But as many scientists had fled continental Europe to escape the Nazis, Britain had become a hub of intelligence. It had scientific brains that were crucial to the project.

A B-29 Superfortress called Enola Gay dropped the Little Boy bomb over Hiroshima at 08:15 on 6 August 1945. Three days later another B-29 called Bockscar dropped a Fat Man bomb over Nagasaki. These marked the first time nuclear bombs had been used in war, and remain the only time.

But a short time after the war was over, the Americans shut both the UK and Canada out of their nuclear testing programme. A spy had been found in Britain who had been sharing secrets with the Soviets. All collaboration ceased.

Dr Chris Hill, a historian of nuclear politics at the University of South Wales, told Forces News: "I think there was a lot of concern, a lot of worry… especially when Russia got its own bomb.

"I think the UK had to put itself in the position of 'who is going to protect us? Who's going to protect the British Isles?'. So having our own nuclear deterrent became quite important.

"Britain wanted to be at the top table. They wanted an atomic bomb with the Union Jack on it, as the Foreign Secretary put it at the time."

The largest tri-service operation since D-Day

In 1952, Britain began its own nuclear testing programme. It lasted around 10 years, involved 22,000 young men and was the largest tri-service operation since D-Day.

If Britain was to become the third nation to have a hydrogen bomb, they needed to test it.

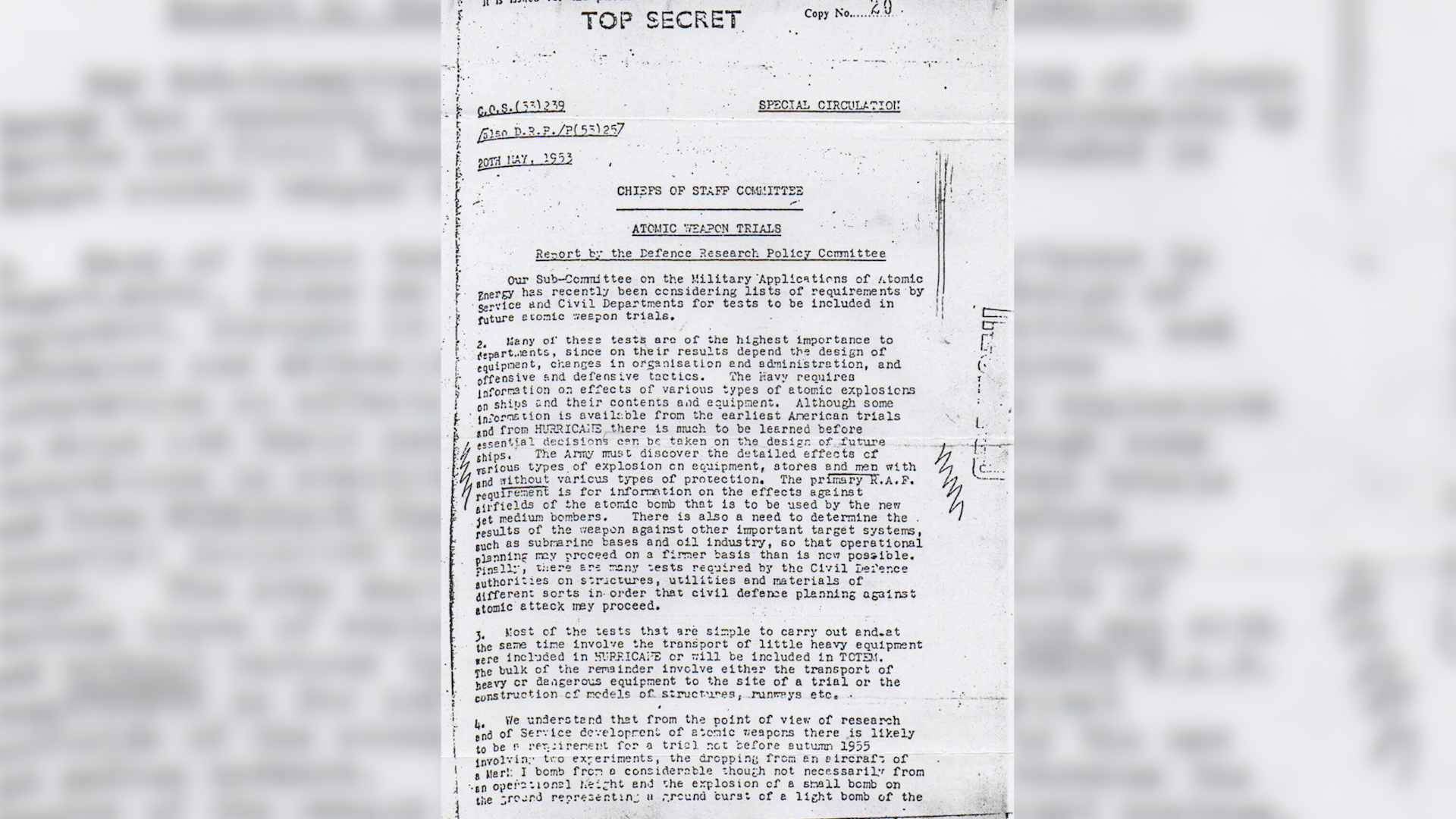

The Royal Navy required "information on effects of various types of atomic explosions on ships and their contents".

The Royal Air Force needed "information on the effect against airfields" and the Army needed to "discover the detailed effects of explosions on equipment, stores and men, with and without protection".

The early tests involved atomic bombs.

These use either uranium or plutonium and rely on fission - where a neutron slams into an atom, breaking it into two smaller atoms. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were atomic bombs.

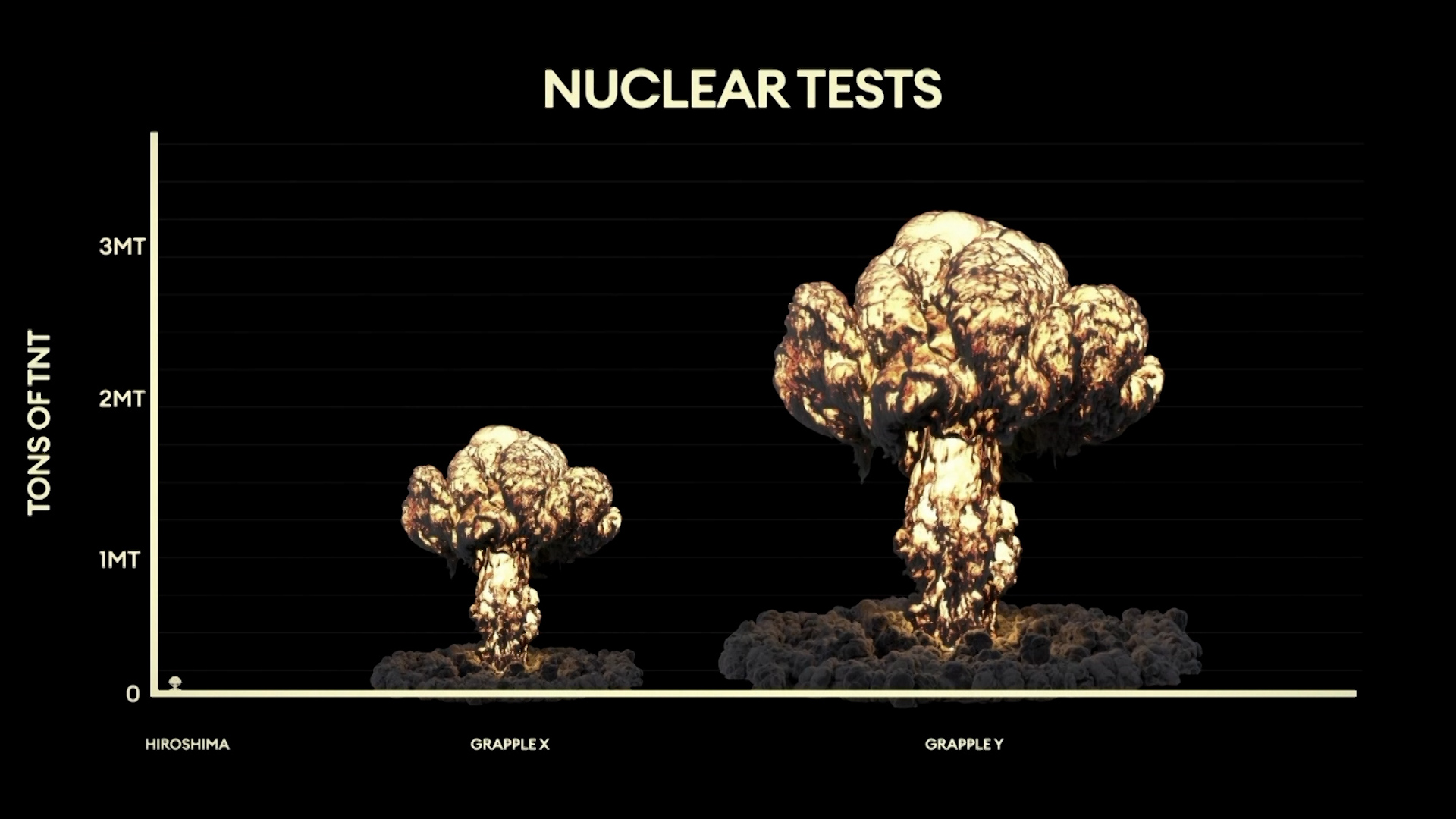

But in Operation Grapple, a series of test carried out between 1957 and 1958, Britain tested its first hydrogen bombs as well.

Hydrogen bombs, which are also known as H-bombs or thermonuclear weapons, rely on fusion - where two atoms slam together to form a heavier atom.

An H-bomb can be hundreds or even thousands of times more powerful than an atomic bomb. But these need an atomic bomb to detonate first to create the high temperature and pressure necessary to start the fusion reaction.

A task 'you couldn't turn down'

Most of the veterans involved in the tests have now passed away.

Some had established cancers and other chronic diseases, with the nuclear fallout they were exposed to being suspected of causing their ill health and eventual death.

The true impact of the tests on their health will never really be known.

But at the time, many of the people taking part in the test programme saw it as an exciting opportunity.

John Robinson was a young pilot in the RAF in the 1950s. His job was to fly through the mushroom cloud minutes after the bomb had been detonated in order to gather data for scientists.

John said: "A notice came round looking for crews to fly special duties out in Australia.

"The requirement was that we all had to be single and that was it. I suppose we were young and foolish in those days and got on with it. It was a task you couldn’t turn down."

Dick Bridges, a former national serviceman who was part of the testing programme said: "I think I knew it was going to be an atomic test, which didn't worry me because at the time that didn't seem all that major.

"We just all thought we were trying to be the best country in the world, the most advanced. So to do something to bring it forward, I was quite happy to do - quite happy."

The 'most evil looking thing I've ever seen'

But while John and Dick had volunteered, Richard Wood was a 16-year-old civilian on board a Royal Fleet Auxiliary ship.

They seemed to know nothing of the nuclear tests until they found themselves off the coast of Christmas Island.

"They said 'You're going to be involved in an H-bomb test'. The crew promptly downed tools. It would have been a mutiny had we been in the Armed Forces," he explained.

Dick describes what happened minutes before the detonation took place.

As a cook in the RAF, he spent most of his time in the kitchen. But Dick and the others involved in that particular test were marched out and made to stand in rank formation with their backs towards the explosion.

They were told to put their hands over their eyes. Dick didn't, merely holding his hands like blinkers either side of his eyes.

He regrets this now.

"If I'd had them in front, I'd have seen the bones in my hands," he said.

There was a countdown after which the men heard "Three, two, one, FLASH, about turn" at which point they all turned towards the bomb and watch. "It was quite frightening," he added.

Some were given radiation dosage meters to wear on their clothes, although these weren't logged against their names, so each serviceman had no idea of the actual dose of radiation he had been exposed to.

On Richard's Royal Fleet Auxiliary ship, the crew had been allowed a few days rest and relaxation in return for taking part in the tests.

"We weren't very happy about being locked below. The hatch came down and 'click, click' and it was locked," he said.

"So we were in a steel coffin in effect… I could just hear this Tannoy-type voice, and we heard 'bomb gone' and then nothing, and then suddenly this flash of light which penetrated through solid steel.

"We felt a push of the ship and I thought 'oh god, if we go over we're in trouble'.

"The hatch was opened and fresh air! Thank god - fresh air! And then I looked at where everybody was stood stock still, no talking.

"The spectre of the mushroom cloud forming and sort of boiling as it were. It was a dreadful feeling. The most evil-looking thing I've ever seen."

"As they said 'flash' – my shadow - it disappeared. And I could feel the heat on my arms and my legs. It was quite worrying at the time. And the sound of that explosion – it was a bit like thunder, but it was constant – constant rumbling." Dick Bridges

"It opened up a new frontier of science," said Dr Wood.

It was about understanding the effects of ionising radiation on people, equipment, animals, ecologies and environments.

There were also specialist groups called 'Indoctrinee Forces' that were tasked with crawling through what was effectively radioactive fallout.

"In retrospect it looks outrageous. There were different standards of medical ethics back then," he explained.

Britain's progress in nuclear testing over the course of a decade prompted the US to rethink the relationship with their friends across the pond.

In 1958 the US-UK Nuclear Defence Agreement was signed – allowing the two nations to exchange nuclear materials, technology and information once again.

Testing alongside the United States resumed from the 1960s through to 1991.

Former pilot John said he felt proud to have taken part in the tests.

National serviceman Dick said he felt terrible for those who had suffered and died, but did not regret taking part himself.

RFA crewman Richard, on the other hand, said the nuclear veterans had simply been used as "fodder".

How crucial were the tests to our nuclear deterrent today?

Dr Hill told Forces News: "I think it's tempting, especially for the Government, to draw a straight line between those tests and our deterrents today."

They were "important for relations", he said, and so are not to be underestimated.

Being the third nation to have an H-bomb was influential in things like securing Britain's place in Nato, but their bombs' value should not be overestimated.