Staying alive: Trainees feel the pressure as they learn to become fast jet pilots

"Mayday! Mayday! Mayday!" Twenty-five-year-old Flying Officer Calum struggles to force out the words between breaths.

Calum and his class of brand-new fast jet pilot trainees are learning the art of pressure breathing – an emergency oxygen system that would be required if they were faced with catastrophic depressurisation at 40,000 feet or above.

It's designed to keep them conscious long enough to make a mayday call and land the plane.

The Centre of Aerospace Medicine is an intriguing place.

Hidden away in a very ordinary block at RAF Henlow in Bedfordshire, this is where new jet pilots come, not to learn to fly a plane, but to learn how to adapt their bodies to cope with the different forces at play high in the atmosphere.

When you've committed to a career where your workplace is largely in the sky and not on the ground, these skills are crucial.

The four-day course has a tightly packed schedule.

One of the most important elements they learn is not to trust their senses.

"We are a ground-based species," says Dr Oliver Bird, a Medical Officer Instructor who has been teaching new jet pilots for more than two decades.

"Our senses really aren't adapted at all well for interpreting the motion or force environments experienced in aircraft."

To prove to the students that sometimes their eyes and ears play tricks on them, the instructors put them in something called the DISO. It's a simulator, but while the students are flying, the instructors throw various scenarios at them.

Sometimes they move the DISO in different directions, sometimes certain instruments are made to fail.

When BFBS Forces News visited the site, Squadron Leader Garth Logan was taking new Flying Officer Ben through the training.

"So when we asked you to roll out we just stopped the DISO – so you've been sitting straight and level – but your ears are telling you you're yawing to the left," he told Ben.

"What's actually happening there – as you come out of a persistent right turn and level off, the inertia of the fluid in the semi-circular canals is sensed as though you're spinning in the other direction, so you get that deceleration of the fluid – and you get that false sense of motion."

Essentially, they must learn to use their instruments and not always trust their senses. Doing the latter could result in, at best, them deviating from their flight path – or, at worst, crashing the aircraft.

Just down the corridor, more students are preparing themselves for a rapid decompression in the altitude chamber.

This simulates what might happen if a canopy or undercarriage door blew off an aircraft.

"We climb to a base altitude of 2,000ft and then quickly decompress them to an altitude of 12,000ft in just three seconds," Dr Oliver Bird explains.

"That leads to pressure changes in their bodies, such as gut gas expansion and even in the middle ear. And they'll also experience those physical changes of noise, mist and a drop in temperature in the chamber before finally we return to ground level – which allows them to test their techniques for clearing their ears."

Sometimes, pressure loss is much less sudden. A crack in a door causing gradual depressurisation is actually a more likely scenario, and incredibly dangerous – as it can go unnoticed. In this situation, hypoxia – lack of oxygen reaching the parts of the body that need it – can creep up on aircrew, leading to them eventually falling unconscious.

The plane then continues flying until it runs out of fuel and crashes.

The student pilots must therefore learn how to recognise the symptoms of hypoxia. These vary from person to person and also change throughout our lives.

They can range from tunnel vision to difficulties breathing, tingling of fingers or just lack of alertness.

The instructors induce hypoxia in the young pilots – just enough so they can recognise what it feels like and would know to reach for oxygen and start descending.

"You've got lots of young, strong, competitive people and sometimes they come in here and they make it a competition," says Major Max Dickey – a flight surgeon from the US Air Force who's here teaching the students during a secondment.

"If you do that, this is how airplanes crash, and so I tell every one of them we just want them to feel symptoms – this is not 'well if I can get down to 50% then I'm great!' – that's not how it works!"

The students will return in five years' time to be made hypoxic once again so they can be reminded of their symptoms and see if they have changed.

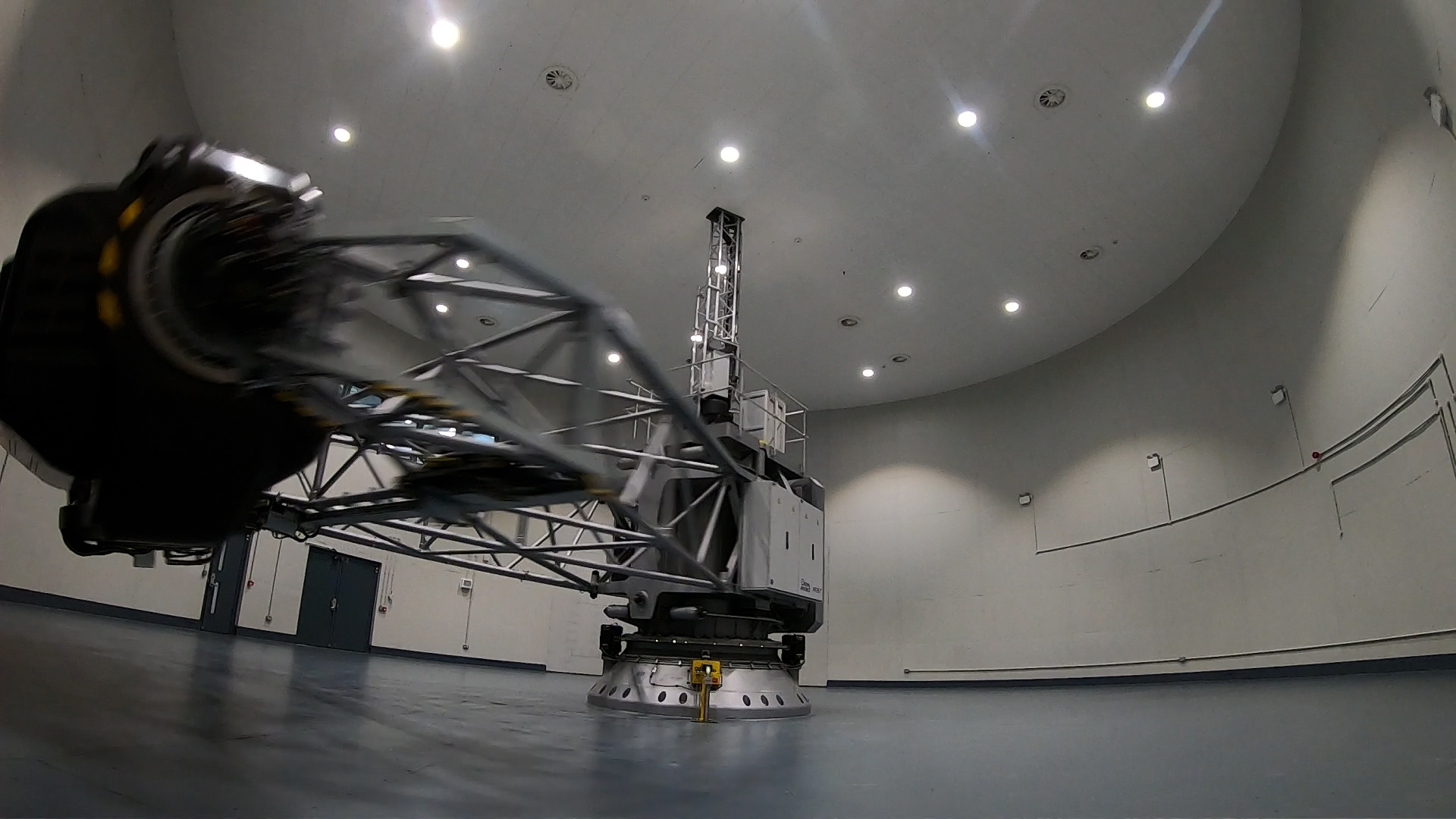

The final part of the course is at Cranwell – home to the RAF's centrifuge.

This is the first time the students have tried flying in the centrifuge and their objective is simple. To fly the plane – and not pass out.

G-force is simply a way to measure rapid acceleration or deceleration.

On their first day in the centrifuge, each new pilot is exposed to 6g for 15 seconds. That's the maximum G they will experience in a Texan – the next aircraft they'll be trained on.

For a Hawk they'll go to 7g – and for the Typhoon and F-35 they'll need to go to 9g.

When the body undergoes G – blood rushes down to the feet, depriving, most crucially, the heart and brain of oxygen.

This would cause the new pilots to pass out pretty quickly, so they need to learn how to prevent it.

There are a number of things that will help them. G trousers are one.

These contain bladders that squeeze the legs – forcing blood back up the body. The pilots must also learn to perform the anti-G straining manoeuvre.

"Muscle tensing is 70% of the battle won already against G," explains Dr Vanesa Garnelo-Rey, another medical officer instructor at the Centre of Aerospace Medicine, "but it's a technique that must be learnt – because that's not how the human body works."

"What we teach them is to curl the toes to engage the calf muscles.

"They can press the rudder pedals as hard as they like and that engages the thighs, imagining a beachball between the knees that you're trying to squeeze the air out of – that engages the quads and the hamstrings.

"My favourite one, which is imagining a walnut up your ass that you're trying to crack open, engages the glutes – and then imagine someone is punching you in the stomach and you're clenching the abdomen.

"And it's all that together in one go. That's just one half – the other is the breathing straining. In medicine, it's called the valsalva. And actually, we all do it if we're ever constipated."

With their time at RAF Henlow complete, the student pilots now progress onto their next stage of training – on Texans at RAF Valley.

"I just love flying," says Flying Officer Jennifer, who studied aerospace engineering at Southampton University.

"There's just nothing quite like it for me – it's almost like a freedom of being in the air... I just love it. It's difficult to describe – I just love it!"