Sitrep: First authorised accounts from SAS Iranian Embassy raid shed light on mission

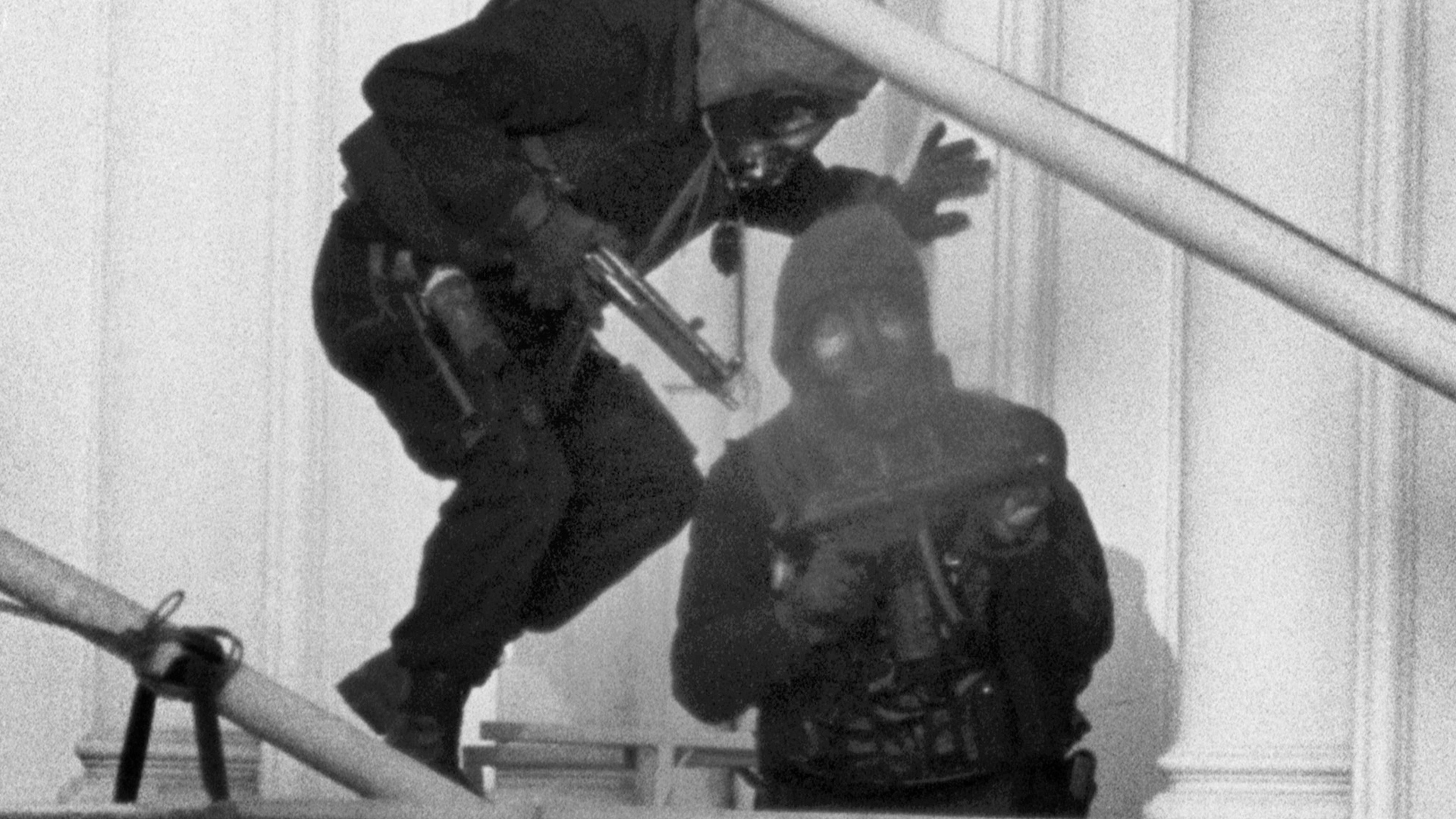

On 5 May 1980, a team of SAS soldiers burst through the window of the Iranian Embassy in London in an attempt to rescue a number of hostages being held by gunmen.

It was a seminal moment for the British military, then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the SAS themselves.

But the mission is shrouded in myth.

Ben MacIntyre's new book The Seige, however, looks to dispel those myths.

His book includes the first-ever authorised accounts from the soldiers involved, now detailed on the BFBS Sitrep podcast – which analyses the top defence stories of the week and is available wherever you get your podcasts.

Mr MacIntyre, the creator of the recent TV series SAS Rogue Heroes, told the podcast how the SAS knew of the situation at the embassy before the Home Office.

In fact, 41 minutes after the terrorists had burst into the embassy, the SAS was tipped off by a police officer, who was a former SAS member.

Mr MacIntyre explained that a man called Dusty Gray had been part of the SAS when it was planning and preparing for a terrorist attack as a result of the attack at the Munich Olympics.

"The British government at the time decided there had to be provision made in case a similar thing happened on British soil," he said.

"So Dusty Gray had been trained.

"He knew about what was called the special projects team, but by this point he'd become a dog handler for the police and he just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

"And then he picked up the telephone to Hereford, to Bradbury Lines, to the SAS headquarters."

B Squadron of the SAS was then authorised to get moving before they had been informed of the incident officially.

"That came about 20 minutes later," Mr MacIntyre said.

The SAS were then held at Regent's Park Barracks before being secretly moved into the building next door to the Iranian Embassy in London.

The mission was planned out, but did not go as expected.

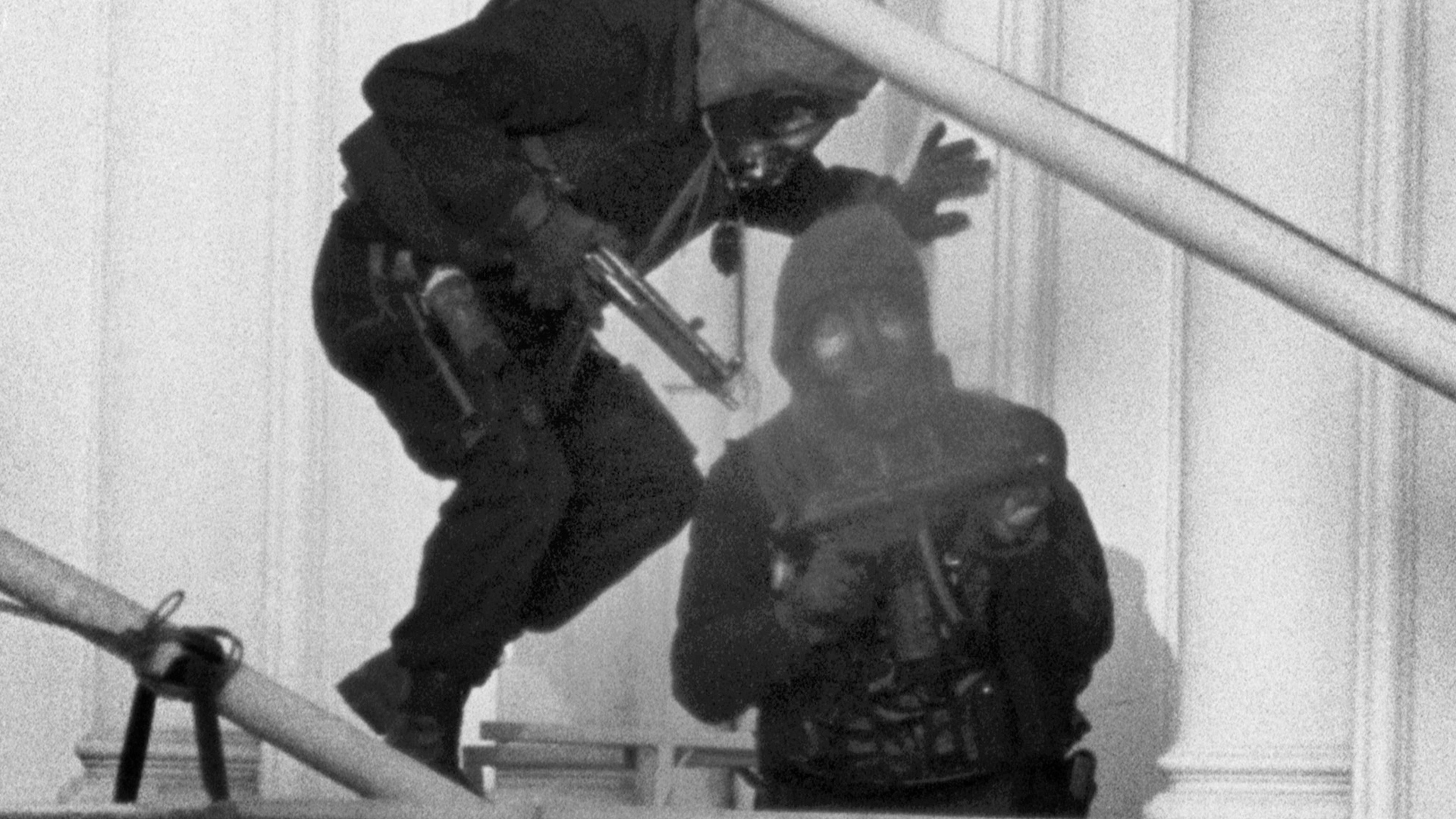

One famous photo captured one member of the SAS team storming the embassy tangled in his abseil lines.

This soldier is Staff Sergeant Tom Morrell, whose first-hand account of the mission is one of those included in Mr MacIntyre's book.

Staff Sgt Morrell was responsible for leading the attack at the back of the embassy, abseiling down onto a balcony on the second floor where it was thought the hostages were being held.

But two things changed the plan – the hostages were not in the building and the leader of the mission, Staff Sgt Morrell, was left suspended above the building.

To make matters worse, the flashbang grenades his team had already thrown through the window had set fire to the room.

"Tom Morrell was suspended above this fire being burned slowly," Mr MacIntyre explained. "He would have burned to death."

His colleagues on the roof who were waiting with a knife to try to cut the rope at the right moment, had to time the swing exactly so that he didn't either fall off the balcony 50ft below or fall into the flames.

"So the timing of that cut and they got it right," Mr MacIntyre said.

"He landed on the floor, stood up immediately, despite being quite badly injured at this point, and he plunged back into the building.

"He led that assault team into the second floor. It was an astonishing act of bravery for which he was decorated."

The mission was considered successful, with the hostages being freed – all but one, who was killed during the raid.

It also had a far-reaching impact, both militarily and politically.

"It became a kind of emblem of Margaret Thatcher's approach to terrorism," Mr MacIntyre said.

"She had been in power for less than a year at this point."

It was probably the most difficult decision she had to make.

"If it had gone the other way and the thing had ended in a bloodbath, as many believed it would, I mean, even the SAS believed that there would be 40% casualties during this assault," he said.

"Had that happened, the story of modern British politics would be very different. The SAS might have been disbanded."

But there were also arguable negatives to the raid – namely the thrusting of the SAS into the spotlight.

"Most people had never heard of the SAS at this point," Mr MacIntyre said.

"They were a shadowy part of the military, they were operating in Northern Ireland, but very not widely known about [and] when they were known about, pretty controversial.

"So they suddenly overnight became celebrities.

"But there are people who feel that it actually did not benefit the SAS in the long run."

He explained that Michael Rose, a former commanding officer of the SAS, is one of them.

"Michael Rose will tell you that actually this made life for the SAS much more difficult because they could no longer operate in the shadows, they could no longer operate with total covert knowledge that they could do it in secrecy.

"And that made, in a way, their jobs much more difficult."

You can listen to Sitrep wherever you get your podcasts, including on the Forces News YouTube channel.