Tri-Service

The British Army Officer Who Pulled Off One Of History's Greatest Cons

Forces personnel are well-known for their black humour. They can often become entrepreneurial out of necessity in all sorts of primitive postings. And they do enjoy winding others up.

But 200 years ago, there was a British Army officer who pulled off one of the most brazen cons in history.

He fooled people into handing over their savings and lured scores to their death in a remote jungle - but rose to the rank of General and was buried with full military honours.

Early Life

Gregor MacGregor was born on Christmas Eve in 1786, into the Scottish clan Gregor. His great-great-uncle was Rob Roy, the outlaw who became a folk hero, and was dubbed the Scottish Robin Hood. Their clan, as Catholics, had been made illegal by King James VI, ostracised from society and forbidden to use their surname. Perhaps his parents were so delighted at their clan name being restored a decade earlier, that they went a little overboard on using it when their son was born. So Gregor MacGregor got his family name twice over.

View post on imgur.comA romanticised depiction of a MacGregor clansman

British Army Record

He joined the 57th (West Middlesex) Regiment of Foot as a junior officer at the age of 16. The Napoleonic Wars were beginning, and MacGregor quickly became a lieutenant. After marrying a wealthy and well-connected admiral’s daughter in 1805, MacGregor paid £900 for the rank of captain, rather than waiting the standard seven years for his promotion.

His infantry regiment was based in Gibraltar, and the captain became unpopular with his men – he was obsessed with dress, rank insignia and medals and forbade those he commanded to leave their quarters in anything less than full dress uniform. There was a short secondment to the Portugese Army, but a biographer relates that a disagreement with a superior officer led to Captain MacGregor’s forced discharge. He formally retired from the British Army in 1810, aged 23. Calling himself “Colonel” and wearing the badge of a Portuguese knightly order, he drove around Edinburgh in a colourful coach, but didn’t gain acceptance into refined society - so he moved to London. There, he styled himself “Sir Gregor MacGregor, Baronet” and pretended he was his clan’s chieftain.

More from Forces TV: The Swift and Brutal End of Richard III

Mercenary

His wealthy wife died in late 1811, and this meant Gregor lost his income. He evidently decided that the life of an adventurer would make him exotically appealing in social circles, so he set sail for Venezuela, which was in a war of independence against Spanish rule. He traded on his former regiment’s name and was given a cavalry battalion to command.

Within two months, the bold officer had married another heiress and been promoted to brigadier-general. But he was on the losing side of the war, so he offered his services to another republican army in neighbouring New Granada. Commanding 1,200 men, the Scotsman was reported to have improved their discipline by teaching European tactics – even though a government official suspected MacGregor was a bluffer.

MacGregor and a force of Venezuelan exiles fought Spanish attackers at Cartagena, New Grenada, in 1815

There were notable successes against the Spanish. Gregor displayed genuine military skill and became feted in South America. He captured Amelia Island, off the coast of Florida, but wouldn’t repay those who’d funded the expedition.

His ambitious vanity became staggering: he hijacked a ship and renamed it in his honour after falling out with its captain; he launched offensives but left his men leaderless and unpaid, many of them ended up dead or taken captive as slaves. He assumed regal titles for himself, while his wife and son were evicted from their Jamaican home and the officer became a wanted man, for treason and piracy.

More from Forces TV: The Battle Of Waterloo In A Nutshell

“Cruel and Deadly” Conman

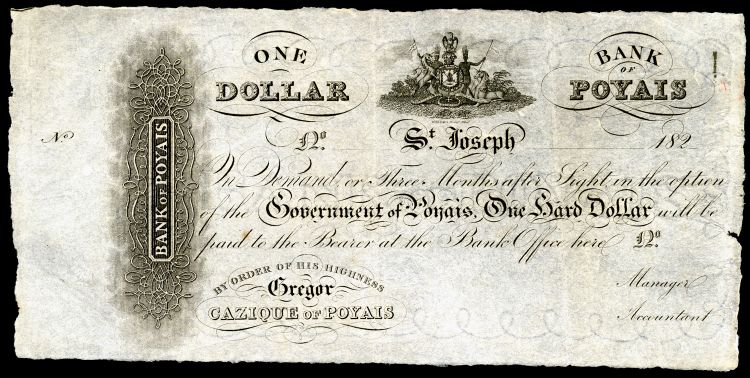

After bouncing back to Britain in 1821, MacGregor claimed that King George Frederic Augustus of the Mosquito Coast in the Gulf of Honduras had created him “Cazique”, or Prince, of Poyais - which he described as a developed colony with an existing community of British settlers. It was all fiction. But Latin America was shifting rapidly, countries were being established, and people fell for the lie that the dashing adventurer was seeking investors and immigrants for this new land.

Hundreds of people put their savings into supposed Poyaisian government bonds and land certificates

With an impressive publicity campaign, swanky headquarters and London Stock Exchange loans, Gregor’s scheme took off. 270 men, women, and children, mostly Scots, set sail on two ships to colonise MacGregor's invented country in 1822–23. What they found there was an untouched jungle, no civilisation, and natives who knew nothing about this “Prince” MacGregor.

The supposed location of Poyais

After months of worry and a suicide, the King was fetched. He revoked the piece of land he’d given Gregor and told the settlers they were illegal immigrants. By now, malaria and yellow fever had taken hold among the encampment on the coast. Some were too weak to leave, but others were transported on a vessel carrying the outraged Chief Magistrate of Belize. Little could be done for the sick. More than half of them died.

A contemporary engraving purporting to show the "port of Black River in the Territory of Poyais"

The authorities in British Honduras sent word to London. Five more ships of hopeful emigrants had already set out for the fictional land. The Royal Navy had to intercept and rescue them. Of those who’d gone through the Poyaisian ordeal, fewer than 50 made it back to Britain.

MacGregor tried the scheme again in France. The British press reported on the deception but some people leapt to the general’s defence. A French court tried him along with three others for fraud in 1826, but convicted only one of his associates. Acquitted, MacGregor attempted further financial fraud in Britain over the next decade.

In 1838, after his second wife’s death, he left his three children in Scotland and moved back to Venezuela.

MacGregor spent his last years in Caracas

He was granted citizenship, restoration of his military rank, and a pension. Gregor spent the next seven years as a pillar of the community in the capital city.

The “hero of the fight for independence” was buried with full Venezuelan military honours in Caracas Cathedral in 1845.

With thanks to the National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Portrait Gallery.