Sarajevo: From Olympics To War

In 1984, Bosnia and Herzegovina, then part of Yugoslavia, became the first country in the Eastern Bloc to host the Winter Olympics. The citizens of Sarajevo were ecstatic. Almost everyone in the city took part in volunteering to make the Olympics a success.

The Games were a triumph.

Bosnians had reason to be proud, everything went smoothly, and Yugoslavia looked well front and centre on the world stage. Skier Jure Franko won the country's first Olympic Winter Games medal. It was a historical moment, and the country basked in glory, global attention, and communal spirit.

Full of Olympic zest, for two weeks in February 1984, Sarajevo felt like the centre of the world.

Eight years later, everyone would be watching Sarajevo again, this time for a very different reason. The War of Independence broke out in Bosnia in 1992, less than a decade after the Olympic Games.

The mountains above Sarajevo, where the Olympic facilities were built, turned into a war zone. The bobsleigh track became a concrete trench, while the podium served as an execution site. The hotels that once hosted the world's top athletes were either burned after shelling or became makeshift prisons.

The area around the 90-metre ski hill was heavily mined. To this day, demining efforts are ongoing. However, most of the Olympic site is safe to visit, and much of it has been reinvigorated. The skiing slopes are fully operational and have been delighting sporty families this past winter. The bobsleigh track is a popular creative outlet for local graffiti artists who have been using 1,300 metres of it as their canvas.

The historical significance of the Olympic venue-turned-war zone keeps drawing scores of tourists who will undoubtedly be back once COVID restrictions are lifted.

The War

As part of the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Bosnian War was a bitter interethnic armed conflict that lasted three years, taking the lives of around 100,000 people and displacing 2.2 million.

From the end of the Second World War until 1992, Yugoslavia was a communist country of six socialist republics – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia.

During its heyday, Yugoslavia was slightly larger than the UK. During communist rule, ethnic and religious tensions within the diverse country were suppressed. However, after it crumbled, they rose to the surface. The population of Bosnia and Herzegovina can be divided into three main groups – Muslim Bosniaks, Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats.

In 1991, Slovenia and Croatia seceded from Yugoslavia, and Bosnia was set to follow the same path when it declared independence on 29 February 1992. The independence referendum was boycotted by Bosnian Serbs, and the results were declared invalid.

War broke out between Bosnian Serbs supported by the Serbian government of Slobodan Milošević, who controlled the Yugoslav People's Army, against the forces of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Croatian troops of Herzeg-Bosnia.

The Siege Of Sarajevo

The mountains where the Olympic site was built are around 25km from the centre of Sarajevo. The close proximity allowed everyone who lived in the capital to feel as if they were part of the Games. The views from above are spectacular – one can marvel at the beauty of the whole city. This also made the mountains a strategic location during the war. From such a vantage point, one can fire on anything or anyone in the city.

The bobsleigh track was turned into a concrete trench where snipers had the perfect place to hide and see the whole of Sarajevo below. Often, they would shoot indiscriminately. It was a terrifying time to be in the city. Women were said to often wear heavy makeup, hoping that the snipers would 'notice their beauty' and spare their lives through their sights.

For almost four years, Sarajevo was surrounded by a besieging military force and almost cut off entirely from the outside world.

Lasting for 1,425 days, the Siege of Sarajevo was the most prolonged siege of any capital in modern history.

The only way in or out was through a tunnel running from a house close to the airport to a garage in the middle of Sarajevo.

From 1992 to 1995, the tunnel was Sarajevo's lifeline.

Edis Kolar and Belma Cuzovic run The Sarajevo War Tunnel Museum which stands above the starting point of the tunnel, around 10km outside of Sarajevo.

According to Edis, the tunnel saved not only lives but the whole Bosnian country and identity.

The tunnel was dug underneath his family home in the village of Butmir due to the proximity to the airport and Mount Igman – the only Olympic mountain that was not controlled by Serb forces.

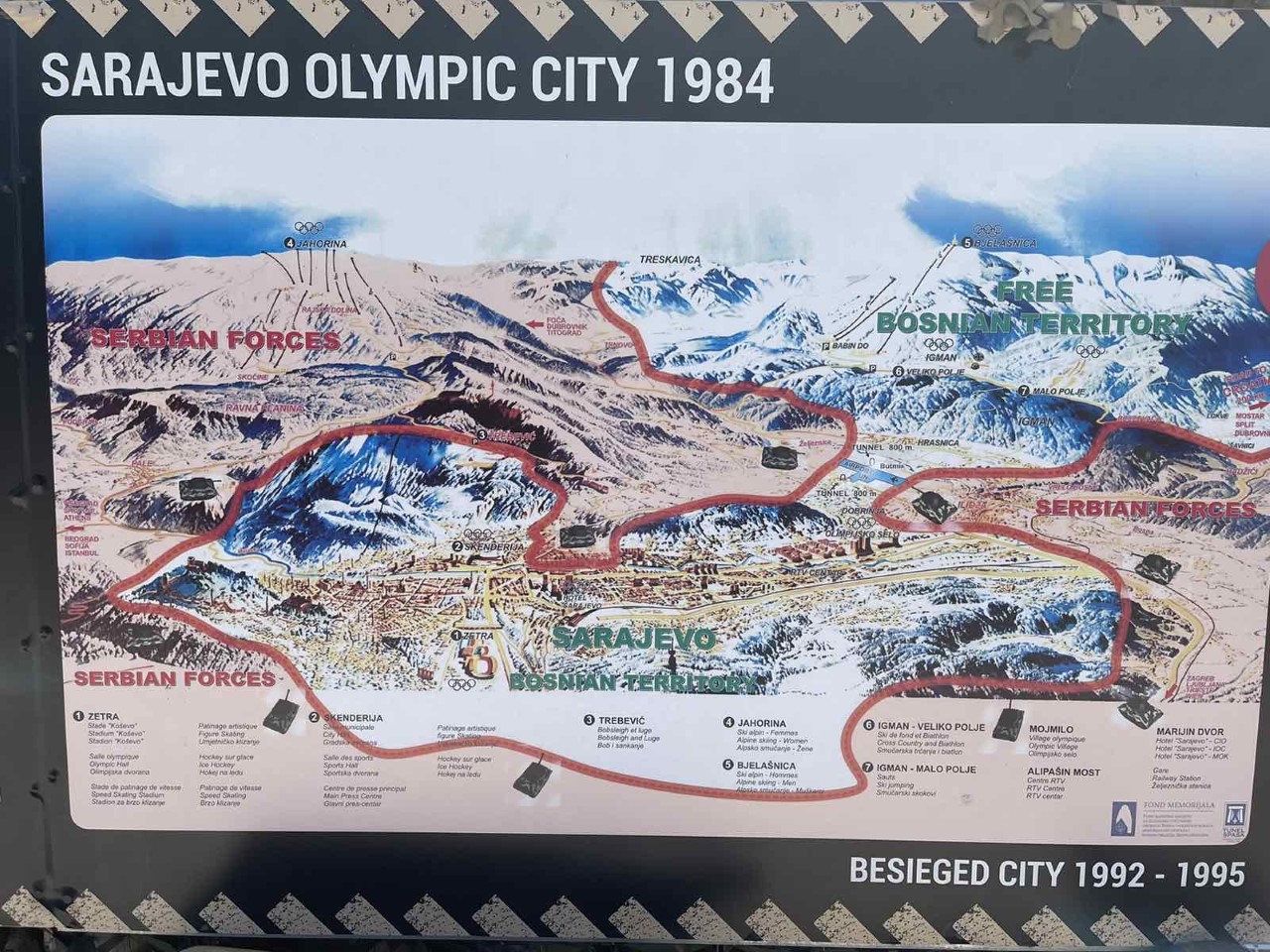

A map of the sieged city proudly hangs, which Edis made from the Olympic City map in the museum. During tours of the museum, they refer to the map to emphasise, as Belma said, "the difference between a city that was the centre of the whole world in 1984 and eight years later, when we became like the prisoners in the heart of Europe."

"Someone just closed our city, and we couldn't go anywhere, and the mountains that represented the beauty of Bosnia now became the points from where the people were killed," she added.

"All the Olympic Mountains were held by the Serbian army, and they were shooting at the people from the places where the Olympics happened … and that is always something that we emphasise when talking with our guests."

Edis wrote on the map "Olympic City 1984" and underneath "1992 – 1995 Besieged City". He admitted that not many foreigners who visit the museum know that Sarajevo was once an Olympic host city. He said that not many places worldwide have had the fortune and privilege to host an event of such magnitude.

The museum curator finds it astonishing how little time passed between Olympic glory and chaos caused by conflict. He said:

"Sarajevo was in the centre of the international community and attention, but they were watching different things, on the Olympic Mountains, in the end, people could watch how Olympic hotels, stadiums and everything else that was built for Olympic Games were burning."

Born In 1984

Belma Cuzovic is proud that she was born in Sarajevo when the city hosted the Olympic Games. Her interest in the Olympics was sparked literally from birth.

Belma's father, Hajrudin Cuzovic, was a taxi driver before the war, which meant he was in the centre of the action during the Olympics, dropping off and picking up the occasional famous face in his cab.

During the war, he became a soldier and came back to the mountains for a very different reason.

In 1997, he took Belma and her sister to the Olympic mountains to humour his daughter's interest. They could not move very far from the main road because of the danger of mines. Belma recalled:

"We were standing on the main road. We couldn't get too near the ski jumps, but he drove us there to show us, and he was talking so proudly, and he was loud, and he was talking about who won the medals and who was there of the famous athletes.

"But at one point, he just flipped, and he started talking on where the trenches were from where they were attacked.

"He was also proud, but the tone of his voice just changed. He was proud because he was a member of our army and defended our country, but it was like he suddenly switched from this, talking about the Olympics and everything that he watched and was a part of.

"And he just started talking about this other part [the frontlines]. That was really hard for him.

"That event was really in my mind for a long time … I can just hear the change in his voice even now. I remember that point when he just went from one topic to jump to another, and it was like he changed."

Belma had spent the whole of the siege in Sarajevo. Today, as a curator of the war museum, many of her memories from that time flow to the surface. She no longer suppresses them. Her father, however, does not like to talk about the war.

The Tunnel Of Hope

Whether president or shepherd, everyone had to go through the tunnel. It was the only way in or out of the besieged city.

In 1994, another chapter was added to Bosnia's Olympic history – it was the first year Bosnia and Herzegovina went to the Olympics as an independent county.

Two years into the war, in 1994, the Olympics were held in Lillehammer, Norway, and to get there, Bosnian athletes had to escape the city through the tunnel built under Edis' family home.

Edis was a nine-year-old boy during the Sarajevo Olympics. His family home was close to the airport, and his strongest memory of the Winter Games was hundreds of planes descending on the city simultaneously. During the war, proximity would be crucial for the army to use Edis' house as the tunnel's starting point.

When the war started, Edis was 17. He joined the war effort as a volunteer after his village was attacked, his house was partially burned, and school was stopped.

The tunnel was the only way to get to Mount Igamn, which was, according to Edis, the most important strategic location for defence because the rest of the mountains and surrounding areas were controlled by Serb forces.

During the 1984 Olympics, Mount Igman was used for ski jump, ski running and biathlon. As a veteran, Edis joked that he and fellow soldiers continued to run there during the war, also with rifles like the biathlon athletes.

Unfortunately, Bosnia and Herzegovina did not win any medals in 1994, but on the other hand, according to Edis, his 'biathlon team' back on Mount Igman started winning that year - 1994 was a pivotal point in the war, after which Bosnian forces gained more power, and the war was over the following year.

Zetra Olympic Hall

The focal point of any Olympic venue, whether Winter or Summer, is the stadium. This is where the national anthems are sung, and the flags of all the participating countries are proudly displayed. This is where it all begins and ends with the closing and opening ceremonies. Described as "ultramodern" and sporting a copper roof, for the Sarajevo 1984 Olympics, this place was the Zetra Olympic Hall.

At the beginning of the war, it was heavily shelled by Serb forces. What was left of Zetra was turned into a morgue. The wooden seats that once accommodated thousands of cheering spectators were broken down to provide coffins for the victims of war who were often buried right outside the hall, turning the area into a war cemetery.

The UN used the hall's basement as a makeshift headquarters where medication and supplies were stored.

If the Olympics Games are a place for the world to come together and be united by the Olympic spirit, then as Edis Kolar put it, what happened to the site eight years later was "100% the opposite". Belma agreed, calling it a "terrible contrast".

Although most of Zetra was destroyed, the foundation stayed strong, and it was rebuilt.

In July 1999, the hall hosted the Balkans Stability Summit, which saw representatives from the region's countries coming together to chart a new peaceful path.

A New Lease On Life

Today, Sarajevo is a bustling multicultural capital city. In 2019, the world's eyes were again transfixed on the city because it hosted LGBTQ+ Pride - one the last remaining countries in Europe that had not hosted an event of this kind until then. There was opposition, but the city also came together to celebrate.

Despite widescale unemployment, Sarajevo has been steadily rising in economy and development since the end of the 1990s. In 2010, the city bid to host the Olympic Games once again.

As Edis Kolar proudly stated, "we have many more hotels now" in the mountains "than during the Olympic Games" in 1984. With 11.5 million dollars of donations from the International Olympic Committee, Zetra Hall was returned almost to its former glory and yet again hosts a variety of sporting events and conferences and concerts.

During the war, the cable car system built in 1959 connecting the city and mountains was destroyed. Today, a shiny new one stands in its place that will transport you from the old romantic part of Sarajevo to Trebević Mountain in seven minutes.

Alongside the yellow tape and red signs warning of mines, reminders that visitors are walking through a former battlefield, are everywhere. Tank tracks are embedded in the roads. Bullets are scattered in the fields. Trenches scar the land, and many of them have been left as they were 26 years ago, littered still with rusty ration tins.

The mountains tell a story of more than just Olympic monuments that turned into the frontlines of war. They remind all that despite chaos, suffering and tragedy, life carries on.

Whether it is supported by a "Tunnel of Hope" or restricted by COVID, it continues, and the Sarajevo mountains that have been full of skiers this winter are testament to that.