The Somme 109 years on: What British soldiers witnessed on the battlefield

To this day, the Battle of the Somme is still one of the biggest battles in history.

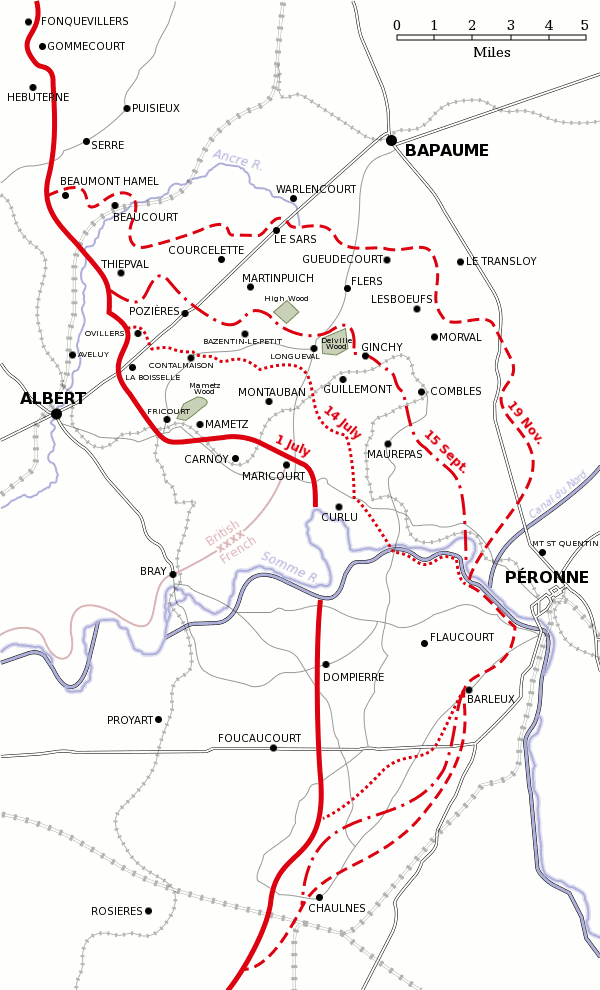

It began on 1 July and lasted until 18 November, 1916, causing a staggering million casualties – with 60,000 killed or wounded on the first day alone.

These are some of the stories shared by soldiers and eyewitnesses who survived the horror.

George Ashurst was with 1 Lancashire Fusiliers in support at Beaumont Hamel.

An enormous mine had been blown and the British artillery bombardment stopped in preparation for the attack.

As zero hour ticked closer and men got ready to go over the top, he recalls in his memoir, My Bit, the terrible German counter-battery fire that then rained down on them.

"We set our teeth; we seemed to say to ourselves all in a moment 'to hell with life' and, as the shout of our comrades in the frontline leaping over the top reached us above the din of battle, we bent low in the trench and moved forward," he wrote.

"Fritz's [the Germans'] shells were screaming down on us fast now; huge black shrapnel shells seemed to burst on top of us.

"Men uttered terrible curses even as they lay dying from terrible wounds, and others sat at the bottom of the trench, shaking and shouting, not wounded but unable to bear the noise, the smell and the horrible sights."

German troops 'destroy' the British

Although the Germans suffered considerably fewer casualties on the first day of fighting, the view from the German trench was just as terrifying.

Shaken by the week-long British bombardment and pre-attack mines, German troops were told that their counter-battery fire would only have a limited effect.

Instead, they were ordered to "destroy [the British] with machine gun fire".

Some guns at Thiepval and nearby Fricourt fired 20,000 rounds of ammunition that day, and some machine gunners' hands were reduced to bloody pulps through incessant use.

It proved to be a slaughter for the British.

German seizure of the high ground at the end of 1914 had given them a defensive advantage over their enemies on the battlefield, but it also inadvertently made tunnelling below no-man's-land easier for the British.

This was because the Germans, being higher, now had to tunnel down and across, whereas their opponents only had to dig in a straight line to get underneath their enemy.

It was an advantage the British exploited on the Somme, and used to even greater effect at Messines Ridge the following year, when they blew up 10,000 German troops.

Brutal fighting

The British were also slaughtered by German survivors in the north of their attack front.

In the south, it was a different story, though at La Boiselle, fighting was still fierce.

Hugh Sebag-Montefiore's Somme: Into the Breach relates how Private J Elliot, fighting with the 20th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers (1st Tyneside Scottish), saw the uncle of the unit's piper and another soldier brutally shot down.

"He was riddled with bullets, writhing and screaming," he wrote. "Another lad was just kneeling, his head thrown right back.

"Bullets were just slapping into him, knocking great bloody chunks off his body."

From across the small battlefield, the German machine-gun company commander remembered how "the bullets fired by our machine-gunners and riflemen smashed like a hurricane into [the British] bunched-up ranks".

"Some of our men climbed up onto our parapets and threw hand grenades at those attackers who were lying on the ground.

In less than a minute, the battlefield seemed to be deserted."

Some unlucky British attackers who made it to the German line in this sector were set alight by flamethrowers, but once the English broke through, German officer Aspirant Brachat remembered how much his side had suffered:

"When the English approached our dugout, I yelled, 'Get out! Face the enemy'," he said.

"I was standing by the entrance when I was wounded by hand grenades.

"Our dugout caught fire. I stood between the English and the burning dugout where the stocked-up ammunition had exploded.

"There was a lot of crying out and screaming, as many of my dear comrades suffocated or were burned to death.

"My only wish was to escape."

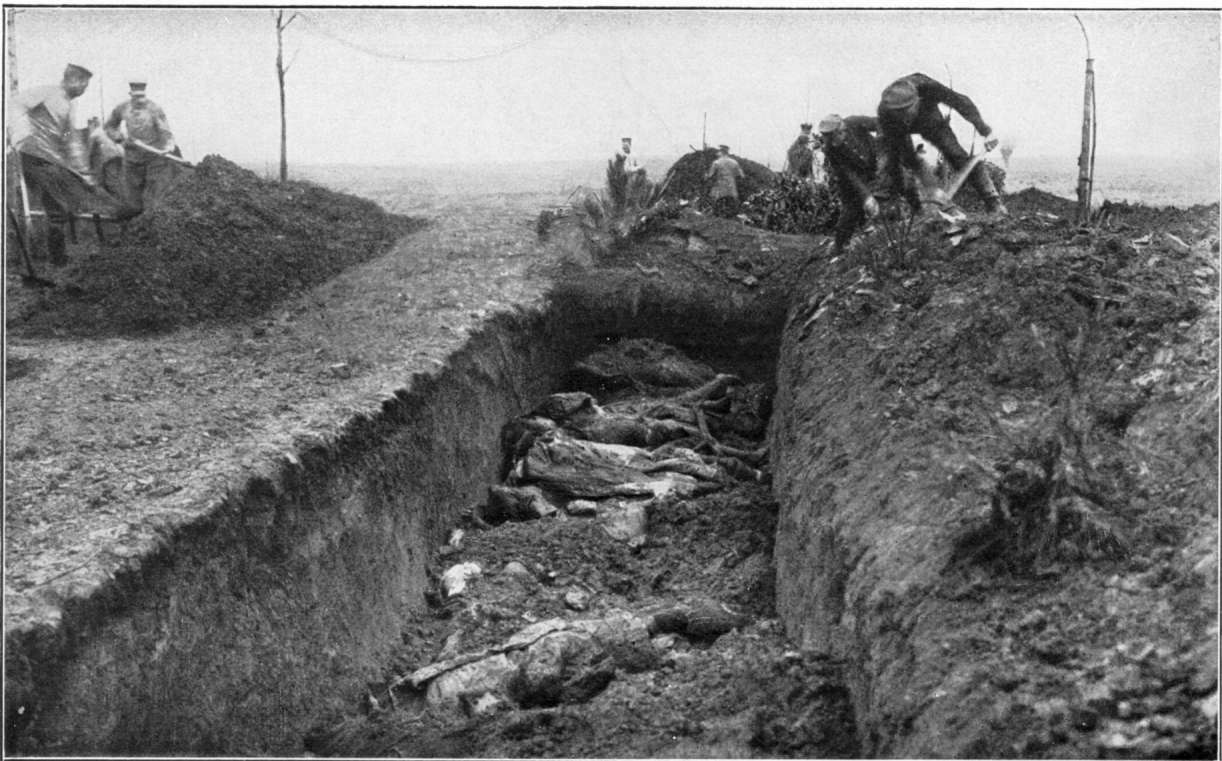

Grim scenes of death

As bad as 1 July had been for British troops, cleaning up after the battle was tough too.

Rupert Whiteman, a 25-year-old lance corporal with the 10th Royal Fusiliers, was ordered to clear up bodies.

"It was a nauseating job," LCpl Whiteman recalled, recounting how the men smoked while they worked to disguise the stench.

"The 'things', who had once been men, were rotting after being left out too long in the hot sun.

"There was no removing of private papers or identity discs, no respectful arranging of limbs."

Even worse, LCpl Whiteman was flung into the air by a German shell and landed in one of the pits where his party had buried the corpses.

The "endless nightmare" was only over when some of his fellow soldiers dug him out.

Similar grisly scenes were related by Captain David Rorie of the 1st/ 2nd Highland Field Ambulance, who also had to deal with bodies later on in the battle.

"[I] could not decide which job was worse, removing the more recently killed ran the risk of upsetting his workers, who frequently came across friends, acquaintances, brothers or cousins," he said.

"Alternatively, there was the horrific task of moving the piles of bones covered with clothes, which was all that remained of those who had been sacrificed on the first day of the battle."

With gains to the south of the battlefront, Allied troops moved north.

For the following five months, British troops – and to a lesser extent, the French on their right flank – shelled and leap-frogged onwards, village by village, ridge by painful ridge.

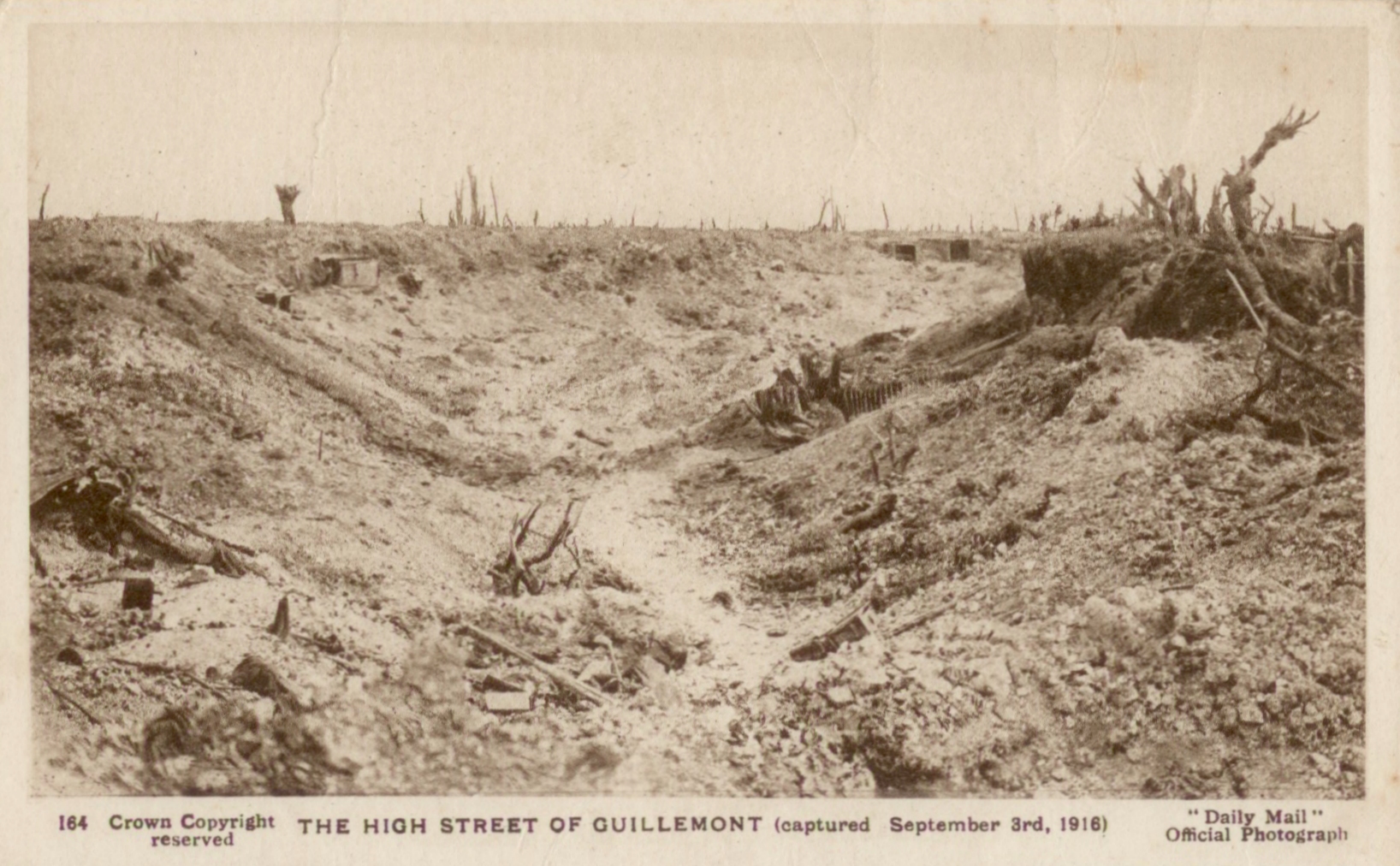

One particularly stubborn battle was at the village of Guillemont.

British historian Gary Sheffield wrote that some observers considered this to be the most effective defensive effort by the Germans during the entire five-month-long campaign.

This was the result of the German High Command innovating its way around problems encountered during the Battle of the Somme.

They eventually withdrew to the shorter and considerably more fortified Hindenburg Line in 1917, a move meant to compensate for losses caused by the onslaught they experienced on the Somme.

Furthermore, they learnt that instead of stubbornly holding ground against endless British (and French) attacks, it was better to be economical with their troops' lives.

They taught them to strategically withdraw in the face of ferocious attack into a network of 'defence in depth', after which they'd counter-attack and retake lost ground.

They planned and built their new trenches with this eventuality in mind, making their lines and concrete pillboxes softer and easier to attack from the rear.

Allied forces needed to capture Guillemont – part of the German second line of trenches and the battle started with a barrage on 30 July.

Having won the war of production, Britain was able to dominate Germany in the artillery exchange and being underground during a British bombardment was every bit as terrifying for the Germans.

Erich Maria Remarque's novel All Quiet on the Western Front depicts troops cowering in dugouts and driven mad simply by the incessant pounding of shells, fearing the always potentially fatal direct hit that could strike at any moment.

"Bombardment, mist, limited reconnaissance, machine-gun fire, indifferent planning and damaged communications made it surprising that any British troops reached the remains of Guillemont," it said.

"Nevertheless, 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers and 18th Manchester captured the frontline trenches of Königlich Bayerisches 22. Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment and penetrated the village."

German troops fight back

Men of the German Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 104, wearing assault packs, emerged from dugouts and cellars to advance by throwing grenades and rushing from shell hole to shell hole.

In a series of small counter-attacks, 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers were all but annihilated and 18th Manchester was progressively surrounded.

The British finally took Guillemont in early September.

Almost none of the original village survived, except a sunken road, obscured from view, well-protected, networked thoroughly with dugouts and, during the battle, packed with machine guns.

This had been the source of so much of the stubborn German resistance.

Both virtually impregnable and undiscoverable, concealed as brilliantly as it was, this explained why so many of the British assaults had been repulsed at that village.

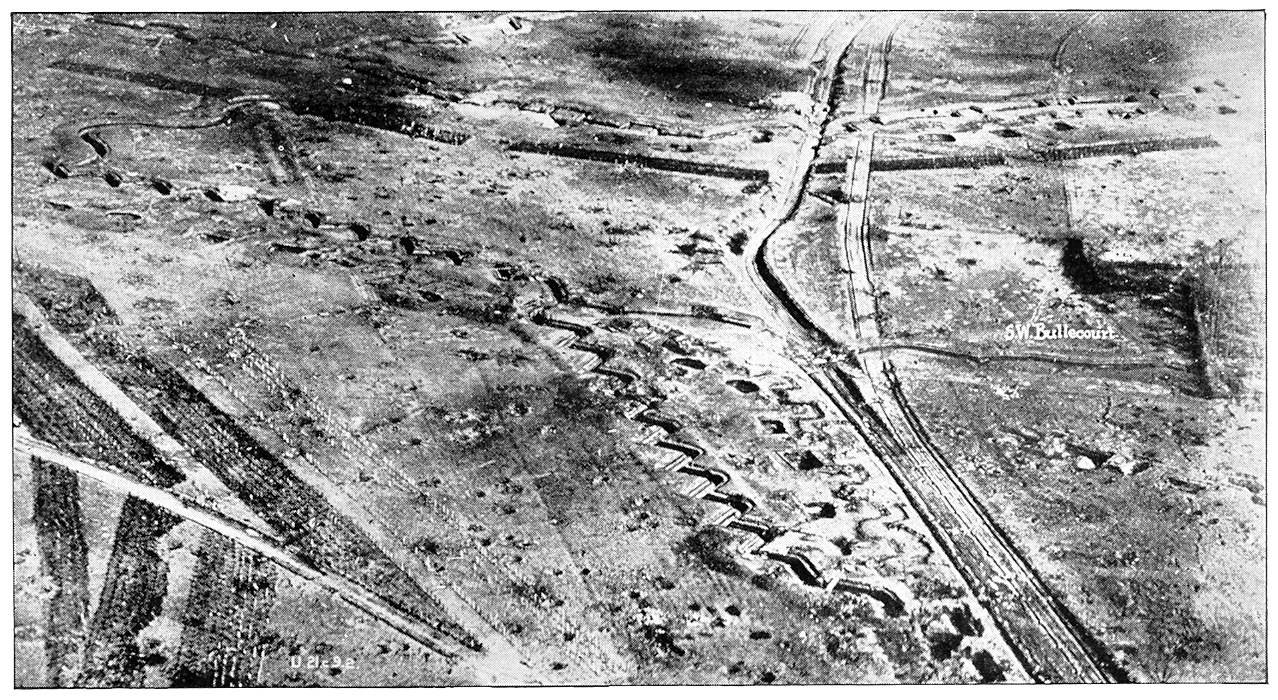

Also bolstered by interconnected cellars and bunkers and bristling with machine-gun nests was the village of Thiepval.

This too had been a British first-day objective, but it proved to be tough nut to crack.

"Over the following three months, the village resisted both attack and bombardment, as thousands of shells transformed the ruins of chateau, church, brewery and houses into a rubble-strewn subterranean strongpoint, dotted with broken trees," said Stephen Bull.

But the British did not give up, and in late September attacked again.

Philip Gibbs was a reporter for the Daily Sketch and witnessed the attack on 28 September.

"It was on the left that our men had the hardest time," he said.

"One battalion [12th Middlesex], leading the assault, had to advance directly upon the chateau – that heap of rubbish and from cellars beneath it came waves of savage machine gun fire."

The British pressed on using a new weapon – tanks, which were often bogged down in mud.

Once on drier ground at Cambrai the following year, British troops could use tanks more effectively.

The documentary The Somme: From Defeat to Victory describes how, at this point, the Germans, quite apart from the sheer surprise and terror they must have felt at first encountering a tank, also began to experience the communication difficulties the British had on the first day.

The British barrage had cut German telephone lines, depriving the commanders in the rear of up-to-date information and the ability to communicate with their men.

In contrast, this time, British Generals were fully informed about the course of the fighting, with reports coming through from artillery observers and planes.

This enabled headquarters to order a re-bombardment of the position still in German hands.

But above all, unlike on the first of July, the senior British command left most decisions to the men on the ground.

Even then, German troops did not go down without a fight.

"Our men had to tackle an underground foe, who fired at them out of holes and crevices, while they remained hidden," said Mr Gibbs.

"They had to burrow for them, dive down into dark entries, fight in tunnels, get their hands about the throats of men who suddenly sprang up to them out of the earth …

"They gave us a good fight on land and underground, this garrison of Thiepval and with a few exceptions they fought honourably, so that our men have no grudge against them now that they are prisoners of war."

From that point, the British fought on to take Hawthorn and Redan Ridges in the north.

"The high ground would give the British a tactical advantage for offensives to be launched the following year, but one last slog was needed.

"It was here that the image of British troops fighting through appalling conditions was born, because as autumn turned to winter and an even heavier artillery bombardment than the first day opened up, the ground was churned up by shells and turned into a swamp by rain, sleet, and even a little snow."

Major General Cameron Shute had taken command of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division before the final battle at Ancre.

His complaints about what he believed was a lack of discipline made him very unpopular.

Despite Maj Gen Shute's complaints, one lieutenant colonel within the division, Bernard Freyberg, performed so heroically in the division's attack on 13 November, that he won the Victoria Cross.

His actions may have been instrumental in helping to win the entire Battle of Ancre.

"The snipers and machine guns were so active that it was dangerous to show your head even for an instant… [they] were quite unaffected by our barrage, which seemed feeble," said Captain Lionel Montagu.

"I saw [Lt Col] Freyberg leap out of the trench and wave the men on.

"Three men followed from my trench. Freyberg was knocked clean over by a bullet which hit his helmet, but he got up again."

The Battle of Ancre ended the larger Somme campaign on 18 November.

The British had taken the high ground that had formed a large part of their objective for the first day, five months before.

In those five months, Britain's role as junior partner in the alliance with France had begun to morph into a senior position.

Although occupied on several fronts, with Austro-Hungarian and Turkish support, Germany's population base of 70,000,000 required the joint effort of France and Britain's combined 78,000,000 population base to check.

And as Britain's Army was enlarged and France's tired after the first two years of war, Britain's role on the Western Front following the Somme became far more important.

It seems that almost every important aspect of war on the Western Front is linked inextricably to the Battle of the Somme.

To learn more about the Battle of the Somme, read 'British Infantryman vs German Infantryman Somme 1916' by Stephen Bull, or 'Somme 1 July 1916 Tragedy and Triumph' by Andrew Robertshaw.

For more on trench warfare, read 'World War I Trench Warfare (1) 1914-16' and 'World War I Trench Warfare (2) 1916-18' by Dr Stephen Bull.

For more on military history, visit Osprey Publishing.