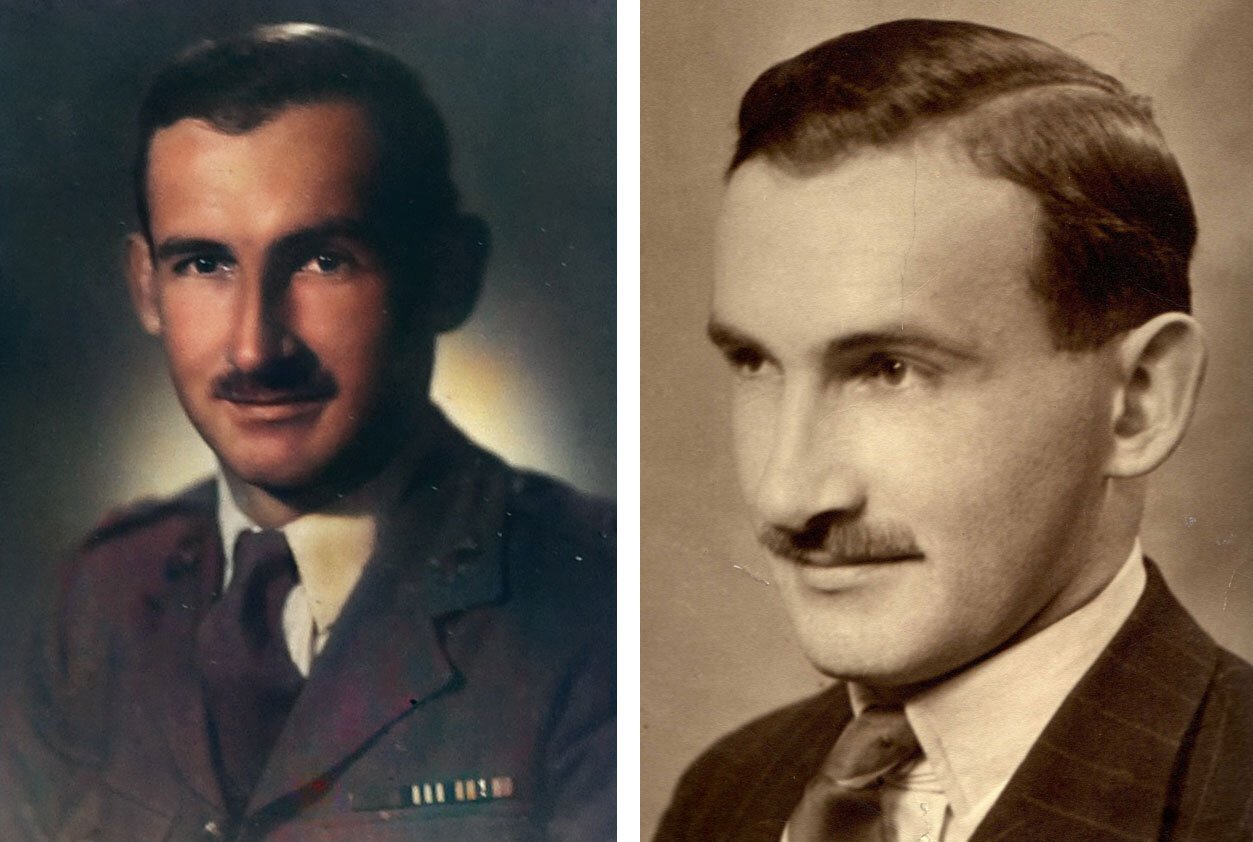

‘Strick’ – A Man Of All Ranks And WW2 Hero

Major General Eugene Strickland certainly knew a thing or two about the army’s command structure.

Starting out as an officer with 1 King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in India, he resigned his commission and left the British Army only to end up in need of work during the Great Depression.

In 1935, Strickland reenlisted as a private and would soon be sucked into World War 2, where he quickly rose through the ranks, taking part in a number of key battles, this time as a member of the Royal Tank Regiment (RTR).

Now, his son Tim, an archaeologist and historian, has become his father’s biographer. Here he covers some of the key aspects of his father’s remarkable military career.

Article by Tim Strickland

Eugene Strickland, known to his friends as “Strick”, had a uniquely interesting life and career.

Born in India in 1913, into a military family which had served on the famed North-West Frontier for generations, young Strick’s world was shattered when his father was killed on the Western Front in 1917.

Rendered almost penniless by her husband’s early death, Strick’s mother was forced to leave India with her young family. Effectively, she set off for a strange country she had never seen but which was always known to her as ‘home’: England.

Through immense courage, discipline and determination, young Strick’s mother achieved a fine education for him and, upon leaving school, he won a scholarship to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst.

From there, Strick gained a Regular Commission into the Indian Army, and, in 1934, departed for India, effectively returning to the land of his background and birth.

Despite this, his penniless upbringing in England had not prepared him for it.

Lacking access to any family allowance, and living in a social world where this was usually necessary for young officers, things quickly went wrong for Strick.

In addition, as well as soon finding himself in debt, he was also alienated by the racism and attitude of snobbery about the Indians that he observed in many fellow officers. He even became a target of prejudice himself, in the form of social aspersions against his Roman Catholic faith.

In the face of all of this, it was not long before the morally courageous young Strick resigned his Commission in the Indian Army. He left the subcontinent in 1935 without even letting his mother know what had happened to him.

The next several months were a period of high adventure. He saw service in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, did temporary work in Paris, then as a stoker in a collier on the trans-Atlantic Rouen-Nova Scotia run. This all ended with a return to London and no job prospects. The country was slowly emerging from the Great Depression, after all, and no permanent jobs were available.

Desperate, Strick, was soon forced to consider a return to the military life.

But that was easier said than done. The army would not accept him back as an officer, so he instead chose to enlist as a private soldier in the Royal Tank Corps.

In a sense, he was being a little bit like his hero ‘Beau Geste’, the protagonist of the novel set before World War 1 who is forced to join the French Foreign Legion as a way out of his own difficult social circumstances. In fact, Strick had tried this twice in his life, but was turned away for being too young the first time, and on the second occasion, he overslept and missed the train due to take him to basic training. So at that point, re-entering the military back in Britain was his best and only viable option.

There followed several years in the Royal Tank Corps (to be renamed the Royal Tank Regiment in 1939), in which young Strick rose through the ranks, becoming a Lance Corporal, Corporal and then Sergeant. In the process, he made a number of friends for life who never forgot him.

Then, along came the war.

Strick’s regiment, 4RTR (the 4th Royal Tank Regiment, formerly 4th Battalion, Royal Tank Corps), departed for France in 1939. It was part of the British Expeditionary Force’s efforts to bolster French and Belgian defences.

All through those strange months of what became known as the ‘Phoney War,’ Strick did well and when fighting broke out there in May 1940, he was given command of a troop of three or four tanks.

There followed a series of remarkable actions which have never really been described in great detail: the Regiment pressed into Belgium, withdrew almost immediately over the border again into France, and then fought in the celebrated Arras counterattack on May 21, 1940.

This action may well have been a primary cause of Hitler’s decision to delay the German advance on Dunkirk by three days, thereby contributing to the much greater success of the evacuation.

Strick performed outstandingly well in this battle, leading his Matilda I infantry tank into and around the deserted streets of Arras alone at one point.

It was here that he encountered a number of German soldiers clustered at the end of a street and chased them down a cul-de-sac, at the end of which they disappeared into a metal barn. Several shots from his Vickers machine gun and one white flag from the Germans later, and Strick had an entire column of German prisoners marching out of Arras before him.

A few days later, near La Bassée, Strick was in the little-known rear-guard action there, in which his tank was the last one covering the withdrawal of the BEF.

When his tank was knocked out, Strick made it northward, on foot, through the enemy-held country. Twice captured and twice escaped, he made it to Dunkirk just in time to get back to England. He would later be decorated for his bravery and achievements during the Battle of France.

He was also re-commissioned.

In fact, from there, Strick’s rise to senior rank was meteoric.

By early 1943, he was in command of the leading tank squadron of the North Irish Horse (NIH), a yeomanry unit repurposed first as an armoured car and then as a tank regiment.

When Strick came to the fore within the North Irish Horse, the traces of which can still be found in the Scottish and North Irish Yeomanry and 32 Signal Regiment, it was serving in the mountainous country of northern Tunisia. Strick did outstandingly well in a series of famous actions, in which his style of leadership and tactical brilliance helped to secure that famous regiment’s success and fine reputation.

Like his battlefield successes, his military career too was characterised by a rapid advance up the ranks and, by early 1944, aged only 30, Strick was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

At this point he was in command of 145 RAC (Royal Armoured Corps), a well-known armoured regiment. However, when the breakout for Rome was planned in the Italian campaign that spring, Strick returned to command the North Irish Horse.

In this capacity, he would lead it in its greatest action and foremost battle-honour: the breaking of the Hitler Line defences, near Cassino.

Decorated with the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his leadership and courage that momentous day, he has never since been forgotten by this famous Irish regiment.

Strick afterwards returned to command of 145 RAC through the bitter and continuing actions in the Gothic Line further up the Italian peninsula, which culminated in the eventual breakthrough to the plains of Northern Italy. This too was a remarkable achievement, and at war’s end, Strick’s decorations, the DSO and MM (Military Medal), were unique in the annals of the British Army in World War 2. The MM was usually given to those in the ranks for bravery while the DSO was awarded to officers for outstanding command. In a few short years, Strick had performed well enough in each of these capacities to win both medals.

Yet the war and its immediate aftermath were not yet over for Strick. Late in 1945, he was posted to command 40 RTR (Royal Tank Regiment) in the closing stages of the prolonged and bitter Greek civil war.

40 RTR were the foremost Territorial battalion of the Royal Tank Regiment and were famed as ‘Monty’s Foxhounds’ for their performance in the Western Desert. Commanding them was in and of itself a great compliment for Strick, and he played his crucial part in supporting the Greek Army in saving Greece from communist tyranny.

When Strick eventually did return home to the UK in the summer of 1946, it was as a uniquely decorated war hero.

He had done astonishingly well and his advance from sergeant to colonel is unparalleled in the annals of the Second World War.

After deliberating on the available options, Strick decided to remain in the Army after the war. In fact, Strick’s equally fascinating, unusual and important post-war military career included close involvement in a series of crucial defence developments: military intelligence and service with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Whitehall. This included guidance on the emergence of China as a great power, involvement in operations in Indo-China, the defence of India, service in the Middle East, with the British Army in West Germany, the de-fusing of flashpoints on the Elbe Frontier with East Germany, and liaison duties with the West German government and armed forces on behalf of NATO.

Among all these achievements, Strick is perhaps most celebrated for his service as Military Advisor to His Majesty King Hussein of Jordan, where he has never since been forgotten.

And, of course, for me personally, the labour of love that has gone into producing the biography of his impressive military career means that not only has he not been forgotten, but that he will go on being remembered for years to come.

For more on the remarkable life and Second-World-War story of Eugene “Strick” Strickland, pick up a copy of ‘Strick: Tank Hero of Arras’ here, already discounted by £5.

And for a look at Strick's role in the development of infantry-tank cooperation during World War 2, as well as an interview with Tim Strickland, click here.